Nearly six months after the deadliest fire in modern U.S. history killed 100 people and destroyed much of Lahaina, there is one positive sign.

The legendary banyan tree in the heart of town — burnt to a crisp in the flames — is sprouting green shoots.

It’s about the only sign of hope. Most of Front Street seems frozen in time.

I saw it with my own eyes, as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers escorted me into the fire zone last Friday for a story for CNBC.

The area has been closed off to outsiders — including media — for a very long time. Why? The reason I’ve been given is that Maui authorities want to show respect for the people who’ve lost everything, including loved ones. That’s understandable, but I can’t help but wonder if they’d also prefer no one see how little progress has been made.

The Corps is just now being allowed in to clear debris, even though the EPA finished removing toxic materials in November. So far they’ve cleared about a dozen homesites, with plans to clean and recycle some of the steel and concrete.

The rest of Maui, meanwhile, is fine and open for business. Tourism is still down about 15% from a year ago, but it’s coming back. An increase in tourism to Hawaii’s other islands has helped offset lost revenues here.

FOLLOW THE MONEY

I went to Maui to see if I could track down some of the cash that’s poured in to help fire victims.

Maui Strong, the largest donation fund, says it’s taken in $178 million and disbursed $88 million. (Here’s a breakdown of where they say the money’s gone.)

Honolulu Civil Beat has a running tally of government and private money coming in, and it estimates that almost $1 billion has been allocated or committed so far.

GOVERNMENT MONEY

About half of the money has come from taxpayers. FEMA tells me that it’s spent $43 million in emergency aid to date, and the Small Business Administration has approved $290 million in loans. Civil Beat outlines other initiatives, like $95 million allocated by the U.S. Department of Energy to harden Maui’s utility grid to prevent future wildfires.

CORPORATE SPENDING

Some of the money for Maui Strong came from Walmart, among the first companies to step up. Its store in Kahului became a place of refuge and reunion during the fires, and many displaced residents or stranded tourists camped in the parking lot during the first week. “We ran out of parking spaces,” says store manager Chris Pierce. He scrambled to bring in extra supplies from Oahu. “We gave away (cargo) containers of merchandise — at least one full container of ice and one full container of rice.” Oprah came in and bought all of the store’s air mattresses and delivered them to shelters.

Since August, Walmart says it’s given away $1.5 million in grants and goods, either from the company or through the Walmart Foundation. Money has gone to places like the Maui United Way, and the company also donated over 30,000 toys to the Salvation Army to “help share the holiday spirit with families on the island.”

CELEBRITY EFFORTS

Then there’s all the celebrity money, and I tried to track some of that, too.

According to the tally from Honolulu Civil Beat, celebrity chef Guy Fieri raised $2.7 million for relief efforts, but when I reached out to his PR contact at Discovery for details, I received no reply.

The People’s Fund of Maui was started by Oprah and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, promising to pay displaced residents $1,200-a-month stipends. The organization told me it’s handed out $50 million to 8,100 residents since September. It took me a while to find a recipient, but I finally tracked down a woman who didn’t want to give her name. “It’s real money,” she tells me. “If you ever meet Oprah, tell her thank you.”

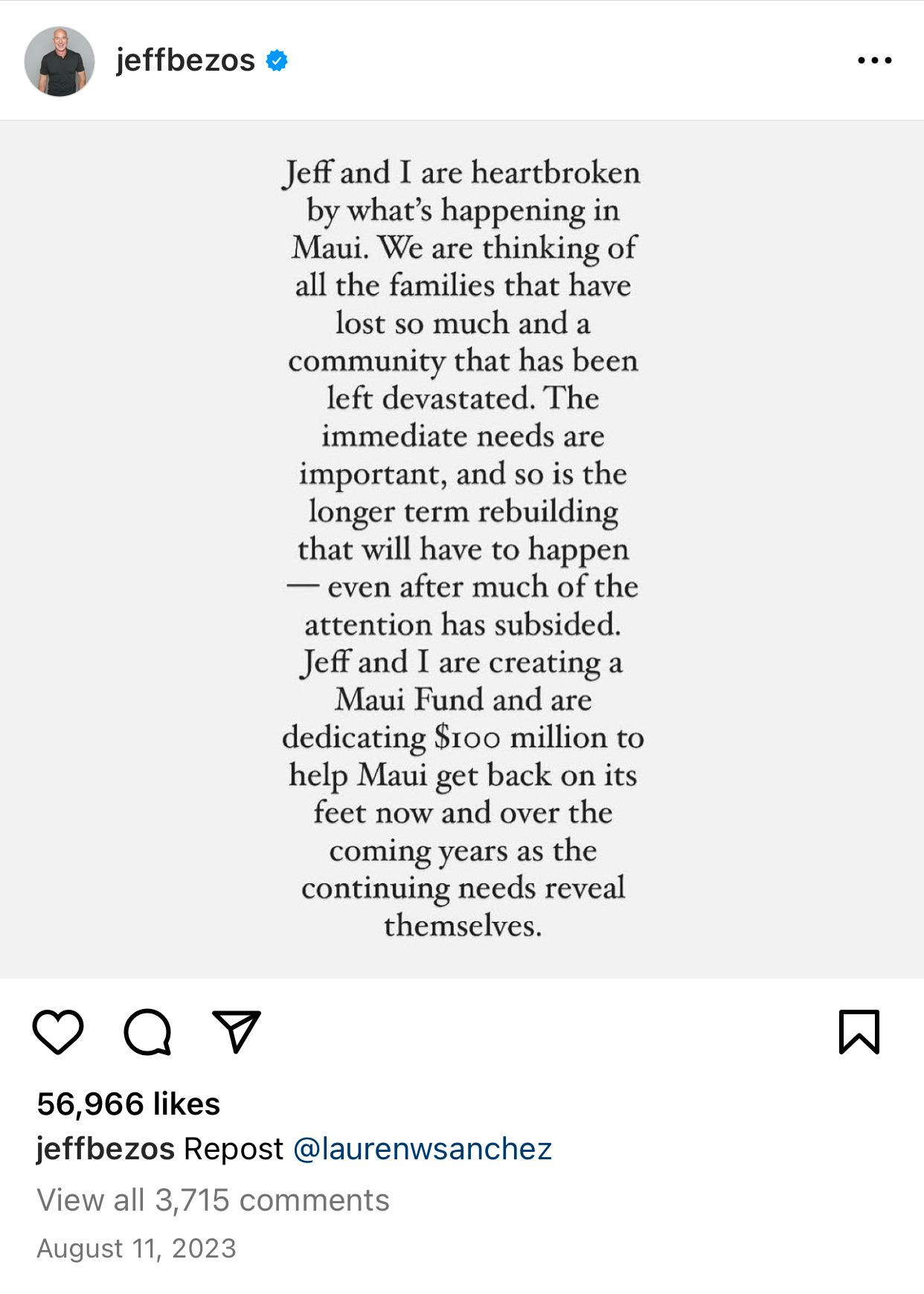

But the number that’s captured a lot of attention is the $100 million promised by Jeff Bezos and fiancée Lauren Sanchez. Bloomberg reported earlier this month that only $15.5 million had been donated, but no one in Maui knew where it went.

Not exactly.

I reached out to Bezos’ representative, who told me, “As the original announcement made clear, the $100 million will be gifted over the coming years as the continuing needs reveal themselves.” He said the $15.5 million that’s already been given has gone to several charitable groups and local watershed partnerships. The Bezos Day One Fund has also announced “the funding of a tuition-free preschool in Lahaina.”

I reached out to a few of the organizations who’d allegedly received some of the Bezos and Sanchez money. The Maui Food Bank put out a statement confirming it received funds, and so did the Humane Society.

“We’ve spent about $2 million on fire-related animal care,” says Humane Society spokeswoman Victoria Ivankic. The money came from a variety of sources. “We expect to spend $25 million over the next two years.”

The Humane Society’s shelter in Maui has handled nearly 800 animals and pets from the fire zone — including Lahaina’s well-known “neighborhood cats.” Donated money is being used to provide veterinary services, food, airfare to fly animals to owners moving offshore, or pay pet deposits for owners trying to find new rentals on Maui that accept animals. “Our main focus is to really make sure that pets and their people can stay together,” Ivankic tells me.

WHAT MONEY CAN’T FIX… YET

Long-term housing remains a critical challenge. A lot of Lahaina homeowners were underinsured. Over 5,000 people are still living in hotels, usually paid for by FEMA and the Red Cross.

A thousand of those survivors are staying at the Royal Lahaina Resort, which is opting to accept a government rate to house locals — including 100 of its own employees — rather than take more lucrative reservations from tourists.

“It’s not about the money,” says general manager Stephen Hinck. I tend to be suspicious when somebody says that, but in this case, the profit motive truly appears to be on the back burner. “We’ve offered up to the Red Cross that we would be available as long as they need us to provide accommodations for the survivors,” he says. “We were the first, and we’ll be the last.”

One survivor living there is Fifita Niu, who goes by the nickname “Nuku.” His home was lost in the fire, along with his work tools. As flames came closer, Nuku tells me he drove his truck through the neighborhood, shouting for people to leave. Then authorities starting blocking escape routes. “I got stuck,” he says. To get out, “I drove on the sidewalk and up the hill.”

He’s grateful to the hotel for giving him shelter, but “it’s not home.”

Hinck, the hotel’s general manager, wonders how long he’ll be housing survivors. “They want to move back to their land,” he says, “but how do they do that? It’s not an overnight fix.”

Hawaii Gov. Josh Green says Maui needs more than a thousand short-term rental units to be converted to long-term rentals providing 18-month leases for displaced residents. “There are 27,000 short-term rental units on Maui alone,” Green said in his state-of-the-state address last week. “If we can dedicate just 10% of these homes to displaced Lahaina families, we can house them all.” FEMA and local government are offering to pay Airbnb owners lucrative market rates if they’ll switch over to housing survivors, and Green is threatening to ban short-term rentals if more people don’t step up.

But on a small island, every action has ripple effects. Renters who are not fire victims fear that when their leases are up, landlords will kick them out in order to take in survivors and accept the government money.

Dany White says it’s already happened to her. She lost her business in the fire, but not her home. In the aftermath, her landlord did not renew her lease. “I looked three months for a two-bedroom for my son and myself.”

Meantime, she’s trying to rebuild the business, Maui Memories. “It was my dream store,” she says.

Dany plans to reopen in March in a new location on Maui in the town of Paia. Insurance has given her $70,000 for lost inventory that she claims was valued at $240,000. The local economic development agency gave her another $20,000, and she started a GoFundMe.

FEMA rejected her application for aid. “I think it’s for homeowners, not business owners,” she tells me. She may seek a loan from the Small Business Administration, though she’s not sure they’ll give it to her. “I still owe $150,000 from my Covid loan.”

Bottom line: Nothing is easy here.

There are more competing interests on this small spit of volcanic land in the middle of the Pacific Ocean than probably anywhere else in the world. Decades ago, it was not uncommon for developers here to pave over sacred burial grounds. Now, the pendulum has swung the other way. Every proposed long-term solution to any problem is debated, delayed, criticized, and met with suspicion.

For example, authorities can’t agree on where to dump the debris that the Corps of Engineers is clearing from Lahaina. The current dump site is only temporary.

Maui officials haven’t even determined the cause of the fire, and conspiracy theories run amok. Rumors race through the “coconut wireless,” and when you walk through the airport, you’re bombarded with “Maui Strong” signs sponsored by personal injury attorneys.

I spoke with legendary surfer Laird Hamilton by phone last week. He grew up in Hawaii and knows the state well. He says the problems being highlighted in rebuilding Lahaina are problems the whole state has faced for a long time. How do you provide affordable housing to the people who live and work in Hawaii? What limitations should be put on tourists, when tourism is the financial lifeblood of the state?

The end result may be that many people who lost homes in Lahaina will do what a lot of Hawaiians have done over the last several years: leave. When I ask Nuku Niu where he expects to live in a year, he answers with a laugh, “Trenton, Missouri.”

If a lot of Nukus leave, Maui will still be here. It will still be beautiful. The whales will still breach offshore, and the turtles will still make their way onto the sand.

But what is Hawaii without Hawaiians?

We may find out.

We saw some of what you described Jane when we visited Kapali in November. The total devastation of Lahaina was heartbreaking. It seems from your report that aid is getting through, and there doesn’t seem to be much corruption of the monies. Let’s hope so. These people have been through so much, I pray for God‘s peace for them. Good news that the Banyan tree is sprouting leaves there is hope.

Thank you for keeping us informed Jane. This story needs to be at the top of the news every so often - otherwise it will be forgotten.