No one sees an earthquake coming, at least not until the last few seconds. Once the quake hits — followed by aftershocks — you soon learn where the damage is. As a reporter, you know where to go.

It’s different covering a storm. You do know the storm is coming. Weather radar tries to predict its path. But forecasting remains an imperfect science, and the storm can change direction.

That’s what happened with Tropical Storm Hilary, and that’s why it’s so hard to be a field reporter covering these disasters. (Fast-moving wildfires are similarly challenging.)

I was assigned Hilary coverage for CNBC, and more than a few viewers this week later asked, “How did you know where to go?” Or, “Why were you on an interstate where there was a rockslide?”

So I thought I’d pull back the curtain on how field reporters like myself make decisions while covering a natural disaster. We’re not in a studio or control room with access to the latest information. We can’t see the live pictures coming in showing locations with the most dramatic visuals. We’re simply driving around listening to radio reports and using our cellphones (when there’s service).

Mostly, we depend on luck.

Here’s a quick rundown of how my coverage for CNBC unfolded.

Jane, like Hilary, kept changing her mind.

Last Friday, my boss emailed me asking if I had any story suggestions related to the approaching hurricane. In other words, would there be damage with financial consequences relevant to the CNBC audience? I looked at Hilary’s projected path and saw that it was heading toward the southeast corner of California.

“That’s where two-thirds of the vegetables we eat in the winter are grown,” I wrote back. “Vegas is another place to watch.”

The Imperial Valley might get hit hard. It’s a low-elevation farming region that grows most of the lettuce, broccoli, artichokes, etc, that Americans eat when it’s too cold to grow them anywhere else. But its water comes mostly from the dwindling Colorado River. With Hilary, farmers were no longer worrying about too little water, but too much.

I reached out to a few people whose names I found by Googling “Imperial Valley farmers.” Yes, that’s my sophisticated research method.

The farmers who answered their phones were polite, but busy. They told me it was all hands on deck trying to harvest and bale crops like alfalfa that were still in the ground — the region grows cattle feed for the global dairy industry. They needed to bale the hay and cover it with plastic tarps to keep it dry once the storm hit. Other farmers were trying to protect their soil from being overwhelmed by flooding so they wouldn’t have to delay planting the winter vegetable crop. Often these farmers are on tight schedules to deliver produce on a weekly basis. Skipping a planting screws that up.

One farmer, Alex Jack, told me it was 115 degrees on Friday at his farm near the town of Brawley. His ranch manager was busy running sprinklers on a jalapeño crop to keep the plants cool enough to survive the heat, even though they knew a deluge was coming that could wipe out the crop. Alex was growing jalapeños for the first time, hoping to profit from the overall shortage.

I told him I might stop by on Sunday, but then he said the situation was just too chaotic. However, he put me in touch with two other farmers — Trevor Tagg and Thomas Cox (“Thomas will be available after church”).

My plan was to drive down to Brawley very early Sunday morning and meet up with cameraman Raul Marin, one of the best photogs in the business. I was concerned about taking the most direct route because it would pass by the Salton Sea, which is below sea level. The road might get washed out, and my little Toyota with it. So Raul and I agreed to meet in San Diego at the home of my husband’s sister and brother-in-law. I would drop off my car there and climb into Raul’s news van, assess the situation in San Diego, and then head two hours east to the Imperial Valley. I booked us two rooms at a hotel in Brawley for Sunday night so that we could be up early Monday to go live.

Saturday night I couldn’t sleep. This is always the case when I’m assigned a big story. The storm could impact anywhere in Southern California, an area covering 56,000 square miles, a region larger than the Netherlands and Switzerland combined. Would Raul and I, in one little van, be in the right place? Would other reporters be at better locations? Somewhere in the back of my head, a faint voice also asked, “Would I do something stupid and get myself killed?” I can be pretty stupid when I’m amped up.

Sunday morning I was up at 4:15am and out the door by 5. It was 300 miles from my home on the Central Coast to San Diego. Flights were being canceled, so I knew I’d better drive.

The highways were empty, even for a Sunday. It appeared that people were heeding advice to stay off the roads because of the storm. It reminded me of the early days of Covid, when everything shut down and you could fly down the freeway.

I didn’t hit any rain until the San Fernando Valley. There was a major downpour as I drove through Long Beach, so I slowed down, along with the five other cars on the 405.

Raul started driving south from his home in Los Angeles to meet me. I asked him to stop somewhere in Orange County to videotape high surf. He did. It was a bust. The waves weren’t particularly impressive, at least not yet.

We met up in San Diego where my brother-in-law, a retired airline pilot, checked various weather programs on his computer. I could see the storm was changing direction — the worst of it would hit further west than originally planned. Was Brawley still the right decision? Should I head to Temecula? Pasadena? Back up to L.A.?

I decided to stick with “Plan A” and talk to farmers. Even if they dodged a bullet, the fact that they’d spent so much money on extra crews and overtime trying to protect their operations seemed like a decent CNBC business story. After I interviewed them, I’d figure out if we needed to drive somewhere else. So we drove east:

We got onto Interstate 8 around 11:30am. Brawley was two hours away. As Raul drove, I listened to local radio reports in San Diego and Los Angeles, trying to get a better idea of the storm’s movement. I reached out to friends with connections in Palm Springs, and one of them sent me a video from her sister, Judy Cressman, showing a swimming pool close to overflowing. Check out the patio sign reading, “Welcome to the desert.”

I contacted another friend in Temecula to see if he could recommend any vineyards. I thought the storm might create havoc this close to harvest. I contacted a couple of the wineries he recommended, but only one answered the phone. “No comment.”

So we kept driving east. I lost cell service as we passed through mountains. I had no idea where the storm was headed.

A creek paralleling the highway came to life. Water was roaring through it. We pulled over to shoot some video.

Okay, now I had some video. This is the point in covering a story when I finally start to relax. I. Have. Video.

What happened next was unexpected.

As we were coming out of the mountains, traffic stopped. We soon learned that massive boulders had come tumbling onto the highway. There was no turning around. The westbound lanes going the other way were not visible.

We waited.

After about 20 minutes, the CHP let us through. There were only four cars in front of us. I told an officer we were going to pull over to get video, and he warned us to park away from the rocks:

We parked, and Raul got out his camera. One CHP officer finally said, “You might wanna move that van,” and pointed to the potentially unstable boulders right above us.

I told you I could be stupid.

I was also very lucky. Not long after we passed through, the CHP closed all eastbound lanes for several hours because of concerns that fast-driving cars would trigger another rock slide. We would’ve been stuck.

It was after 2p by the time we reached Trevor Tagg’s farm in El Centro. The wind was rocking the van as we drove. Trevor warned us to park right on the road, because the van might otherwise slide down into the mud. (Fun fact: He also told me the road is nicknamed the “Fentanyl Highway” because it’s a major drug route in and out of Mexico.)

After Trevor explained the situation at his farm — how they’d pulled alfalfa out ahead of Hilary to harvest the seed — we then rushed over the Thomas Cox’s farm closer to Brawley. He had his fingers crossed that his frantic prep work to build up seed beds would help the soil dry out quickly after the storm passed. He even had sprinklers put out, because after a deluge, a light sprinkling can soften up the topsoil for planting.

There wasn’t much rain while I was there, but there was plenty of wind. The breakup in the audio of my interviews did more to tell the story than anything I could say. Nice ponytail wind gauge!

After the interviews, I decided to drive to Palm Springs, 100 miles north. It sounded like the streets were flooded there, and I figured it was an iconic place that CNBC viewers would be familiar with.

It took a couple of hours. There were stormy waves breaking along the Salton Sea, something I’d never seen. Power was out at every truck stop along the way (no food or potty breaks!), but at least I had intermittent cell service. I tried to cancel our hotel rooms in Brawley, even though I was inside the no-cancellation window, but I couldn’t get through.

We arrived in Palm Springs by early evening. The place was a ghost town. Several intersections were flooded, and Raul calculated the risks of when and where to drive.

Once downtown, we tried to figure out what would make a good backdrop for the next morning’s live shots. My first appearance was scheduled for “Squawk Box” at 3:20aPT.

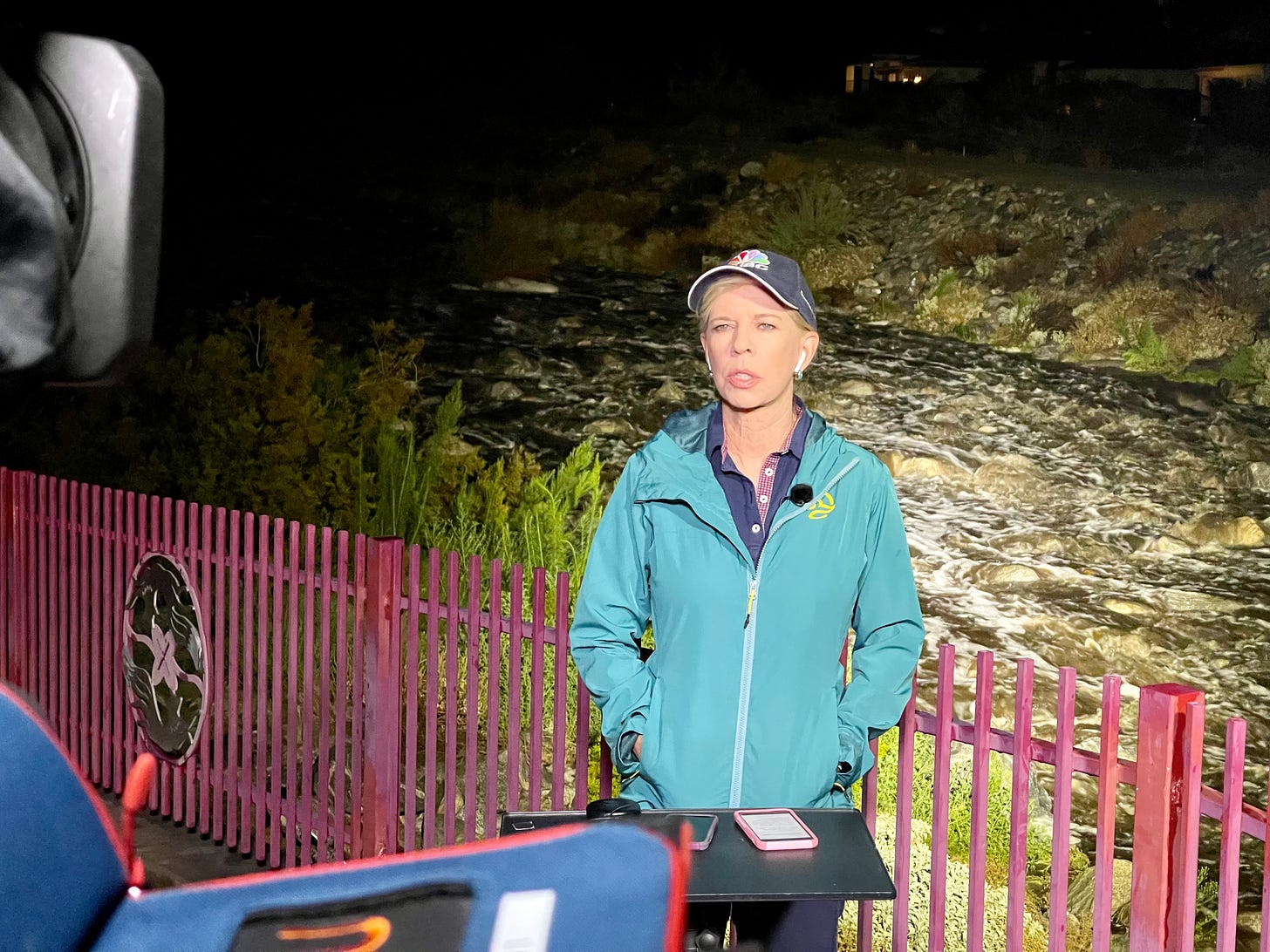

Should we go live on Palm Canyon Drive where there were a few sandbags in front of retail stores? Maybe in front of the large statue of Marilyn Monroe? As we drove around, Raul noticed a normally dry creekbed that was now a raging river powered by water coming down from the San Jacinto Mountains, where nearly a foot of rain had fallen. It was noisy and visual, and we knew it would still be that way in the morning. That would be our backdrop.

It was time to find a hotel, feed the video, eat some food, write my first story, and grab some sleep. Thankfully, the Hilton had rooms and a functioning restaurant.

I was up at 1:45a on Monday and out the door by 2:20. I continued to check for the latest updates on the storm, and the producer working with me back at CNBC headquarters scoured the network video feeds for anything interesting, especially as we learned that Hilary had strangely veered further west. At one point, its eye was over Dodger Stadium.

I reported on the air three times, and we wrapped up around noon. Only then did I notice that the live shot location behind me had been the scene of something … dramatic. I hope she’s okay.

In the end, I was very lucky. I found farmers willing to meet me for interviews as we struggled to stand in the wind. Most have since told me that Hilary’s damage was minimal, at least on the U.S. side of the Mexican border. I was also lucky because Raul and I found flooded creeks and streets to capture on video, and my cellphone video of boulders on the highway has been viewed nearly 450,000 times on X.

Also, the hotel in Brawley never charged me. I think it may have lost power and closed its doors. Pivoting to Palm Springs was another lucky move.

Most importantly, Hilary wasn’t nearly as bad as expected. That doesn’t necessarily make for a good news story, but it does make for good news.

Enjoyed "this is what it's really like..." narrative. How genuine you are and your sense of humor continue to shine Jane.

Your usual excellent reporting. I watched a CNBC report by you and saw that pony tail flying. Gave me a few chuckles.