L.A.’s Future (And Why It Matters)

There’s another red flag warning in Los Angeles this week, even as the smoke hasn’t cleared from the Palisades and Eaton fires which started two weeks ago. Those fires are still burning, and as of today, 27 people are dead and an estimated 12,000 structures have been destroyed.

It must seem like the whole place has gone up in flames, but it hasn’t. What does the future hold for the local economy? You should care, no matter where you live, because Los Angeles County contributes over $800 billion to U.S. GDP, more than any other county in the U.S. (It’s also the largest county by population, with nearly 10 million people.)

Last Friday was the anniversary of the Northridge earthquake. The 6.7 shaker hit before dawn on January 17, 1994, killing 57 people, damaging or destroying 82,000 structures, and temporarily displacing 125,000 residents. Losses were estimated at $35 billion.

Here’s a throwback video of yours truly covering the quake. As you can see, I didn’t have time (or electricity) to make myself “camera ready” that morning:

It took years to recover, but mainly because the L.A. economy was already suffering from the loss of an estimated 127,000 jobs due to the defense industry downsizing. “The earthquake was just kicking a sick dog,” says Chris Thornberg, a long-time economic forecaster who co-founded Beacon Economics.

Yet in the months after the quake, unemployment didn’t go up. It dropped. And even with the loss of tens of thousands of homes, housing prices didn’t go up, either. Instead, they continued their march downward due to other issues (like the loss of defense and aerospace jobs).

So Chris — who was under an evacuation warning last week when we spoke — is surprisingly upbeat about the local economic outlook. He says L.A. after the fires in 2025 is not L.A. after the quake in ‘94. “I don’t want to diminish the suffering of the people here, my heart bleeds,” he says, “but the L.A. economy is in good shape. It really is.”

Chris has been studying disaster recovery going back to 9/11. “This is what happens,” he tells me. “There's a very brief period of reduced consumption and economic activity during the cleanup, and then there's a surge in economic activity during the rebuilding. And then you’re back to normal.”

He points out that in the recent fires, the loss of 12,000 structures is a relatively small number per capita in a region of 3.6 million residential units. For example, three massive fires destroyed nearly 7,000 structures in Napa and Sonoma counties in 2017, an area with less than one tenth the population of Los Angeles County. In the immediate months after those fires, Chris says prices went up for homes and apartments, but by the beginning of 2019, prices were falling. “Even there,” he tells me, “we saw a rapid recovery.”

This wasn’t the forecast I expected to hear. It’s certainly not what I’m hearing from Joel Kotkin, another long-time L.A. analyst who is the Roger Hobbs Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University. “L.A. and Southern California have been pretty consistent underperformers for at least the last five years,” he tells me. “I don't necessarily see the prospects getting a lot better.”

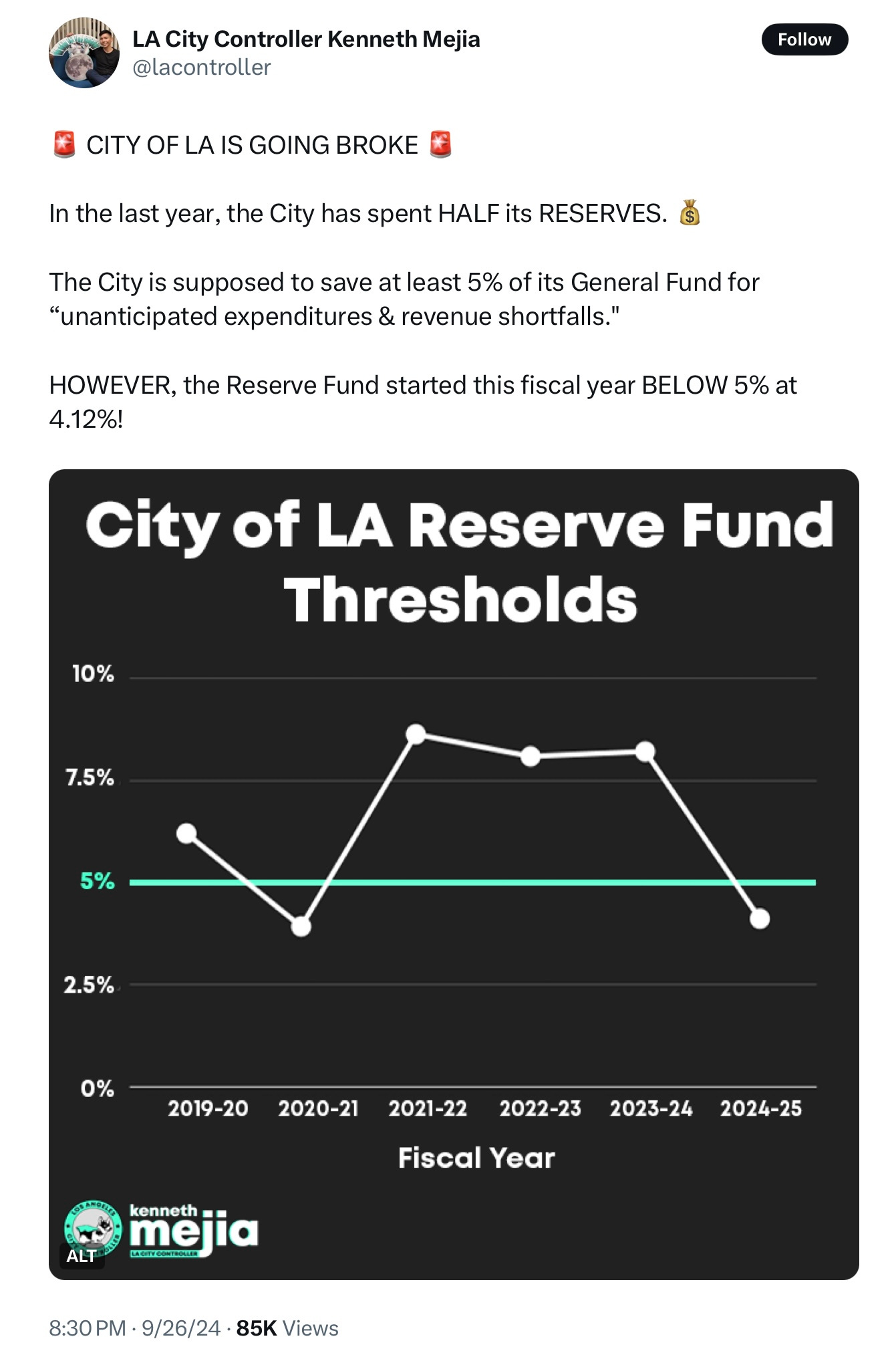

Before the fires, L.A.’s economy was only expected to grow one-half of one percent in 2025, according to estimates from the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp. Production in Hollywood has not recovered from the strikes. Budgets have been cut as the city controller consistently reports that Los Angeles is running a deficit. Here’s one of his posts on X last September:

Joel recently wrote that L.A. “suffers among the highest poverty rates in the state.” It builds far fewer new housing units per capita than almost every other major city in America, and it has the second largest homeless population (behind New York City). He blames one-party rule that has forced out “dirty” manufacturing jobs along with much of the middle class, leaving a city populated by very wealthy people and very poor people.

He says smaller cities within the county are doing much better than the City of Angels itself, partly because local leadership is held accountable. You might run into the mayor at Starbucks. Joel says it’s not like that in L.A. “You could parade the L.A. City Council down any street, and nobody would know who these people are.”

Will things get better after the fires? For all the outpouring of help, as neighbor helps neighbor, I keep reading stories about looters and canceled insurance policies and “real estate vultures.” Then there’s all the news about price gouging. Any rent hike of more than 10% after a declared disaster is illegal under state law, and yet it appears some landlords are taking advantage of the situation.

Chris Thornberg isn’t buying it. He says a local reporter asked him about skyrocketing rents, and Chris pressed for details. Who? How many units? Where? The reporter said people “self reported” about 200 units with usurious hikes. Thornberg replied, “How many units are for rent in L.A. right now?” The reporter didn’t know. “I said, ‘Let me look on Zillow… 24,000 units are for rent.’” Two hundred incidents of gouging out of 24,000 units is less than one percent. Chris laughs recalling the conversation. “Why do you just assume that anybody who owns a property is, by definition, a Bond-type villain who goes out of his way to be as evil as humanly possible on a minute-by-minute basis?”

The Los Angeles DA is threatening to prosecute any landlords who gouge. But as of this writing… no one’s been arrested. The state’s Attorney General is also threatening legal action but would not disclose how many actual complaints he’s received.

What has surprised Chris is the lack of leadership. “Fires are something that California understands. The real question is, why the hell were we surprised? Why weren’t we better prepared? And the answer is because local government in California has been so obsessed with social and environmental justice that they've forgotten the nuts and bolts of public safety.”

Joel Kotkin couldn’t agree more. He says local leaders blame everything on climate change, which he calls “the great ‘Get out of Jail Free’ card.” He hopes the fire will bring a reset of priorities. “Maybe you don’t listen to every environmental group that can find some obscure insect so that you don’t clear brush,” he says (or a shrub that halted a wildfire prevention project in the Palisades). “I mean there has got to be some kind of reckoning.”

The biggest problem in Los Angeles, Chris Thornberg believes, is the same problem it had before the fires: the availability of affordable housing. According to Realtor.com, the median price of a home sold in Altadena last month was $1.3 million. In Pacific Palisades, it was $4.2 million. That’s not affordable. Chris blames local and state governments for consistently paying only lip service to fast-tracking affordable supply. “When push comes to shove, they basically only interact with the NIMBYs.”

Any attempt to create denser housing in the burn zones will be difficult. The Governor’s executive order to waive environmental rules for rebuilding only applies to structures that “do not exceed 110% of the footprint and height” of the homes they’re replacing. So it’s unlikely that extra supply will be added.

The second problem, Chris says, is access to insurance. It’s true that companies like State Farm have canceled policies. The company even canceled his policy.

“But be that as it may,” he says, “if you have a mortgage — and 70% of homeowners in L.A. County have mortgages — you have to be insured. If not, you will get a very nasty note from your bank saying, ‘We're buying insurance for you because you're not allowed to not have insurance with your mortgage.’”

Chris’ own insurance is now through the California FAIR Plan, a plan funded by the dwindling list of private insurers operating in the state. It’s the insurer of last resort. It’s also currently underfunded and may need a taxpayer bailout. Plus, the plan caps reimbursements at $3 million, which seems low, considering what many of the destroyed homes are worth (though most of the value of a house is in the land, not the structure).

To convince more insurers to cover California, the state’s insurance commissioner recently announced that companies will be allowed to price in more risk. Premiums will go up. “That’s life,” says Chris. “We've never required businesses to operate at a loss in the United States.”

But even with all that, he thinks Los Angeles will thrive despite itself. “We have a lot of good things going in Southern California right now.” Port container traffic is up 20%, though some of that may be due to importers front-loading supply ahead of Trump tariffs. The unemployment rate is 5.6%, higher than the national rate of 4.1%, but historically low for the region.

The New York Times, writing last week about L.A.’s long recovery, said the region’s “wealth and industrial diversity, along with other natural advantages from geography and weather, may allow Los Angeles to stave off a worst-case scenario” (emphasis mine). The Times pointed to analysis from Goldman Sachs forecasting a loss of 15,000 to 25,000 regional jobs in January because of the fires — “That’s less than the hit from last summer’s major hurricanes, after which people quickly returned to work.”

Joel Kotkin thinks those numbers are not taking into account the loss of faith in local government in Los Angeles, something he just wrote about. A recall petition is demanding that Mayor Karen Bass resign. Others want Fire Chief Kristin Crowley to quit. “I think that is a real problem,” Joel says, “not necessarily just for voters, but for an investor. Am I going to invest in a city that can't even protect one of its most elite neighborhoods, much less working-class Altadena?” He hopes the fires will be a catalyst for change at City Hall and Sacramento. “The big difference may be that the wealthy progressives who’ve bankrolled the Mayor and Governor may realize that maybe this kind of government doesn't work so well.”

He believes one positive change in power in Washington D.C. is that Republicans may only send aid to California with strings attached. Critics will call that a purely political move, but Joel tells me “I don't give a sh*t about the political ramifications. I want to know what happened and why, and how you can change it.”

Meantime, Chris Thornberg remains optimistic. He says Los Angeles will rise from the ashes and continue to perform. And by the time the Olympic Games arrive in 2028 — assuming they’re not canceled or moved elsewhere — many of the fires’ physical scars will have healed. Maybe even some of the emotional ones, too. “Remember, rebuilding is a lot simpler than building,” Chris says. “People are a lot tougher than we give them credit for.”

In the meantime, a lot of people need help NOW. My go-to charity is always the Salvation Army, which truly “does the most good” with the lowest overhead. Donate here.

I don’t care that you’re a Dodgers fan. You give good insights 🤙🏼

Very Informative. Thanks for posting!!