Thanks for stopping by Wells $treet, where I’m always asking why everything costs so much. I have a beef with beef prices in particular. I encourage you to subscribe to this newsletter and follow the mysterious ways money moves behind the headlines. It’s free! Unlike that juicy hamburger dribbling down your chin which cost more than your car insurance! And rant along with me on social media — Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn.

💰💰💰💰💰

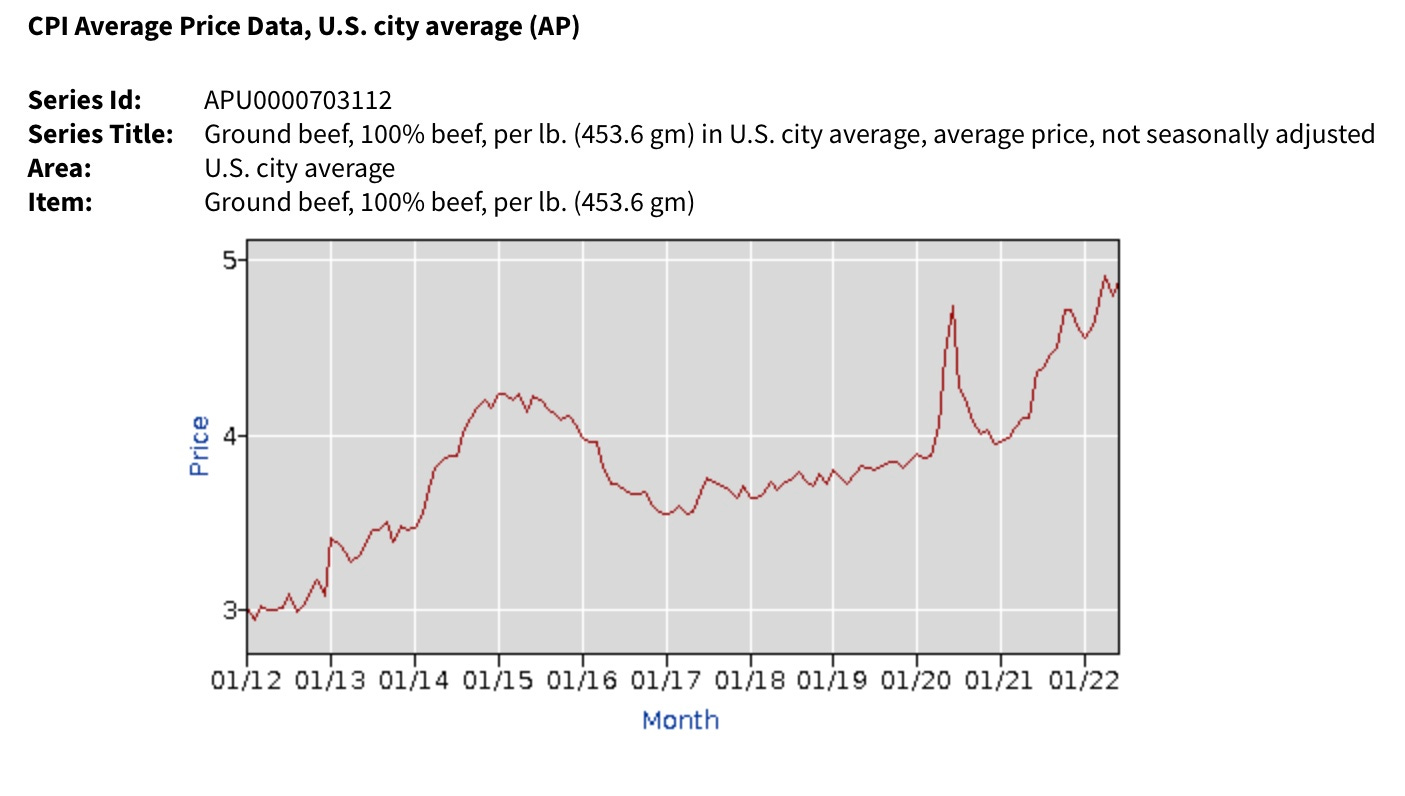

Back in 2019 — before Covid and the supply chain crisis — the average price for a pound of ground beef was $3.80 at the grocery store. A year later, at the height of the pandemic, the price shot up nearly a dollar to $4.70.

Some people thought such inflation was transitory.

Those people were really, really wrong.

Right now ground beef is even more expensive than it was when the world shut down. It’s currently averaging $4.90 a pound.

Yet Americans keep buying it. Demand for beef remains strong in the face of high prices. It’s a bit of a mystery.

But here’s something crazy: Despite high demand and high prices, cattle ranchers are preparing to produce less beef... which goes against the basic laws of economics. More on that in a minute.

USDA price chart for ground beef.

America’s Lonesome Cowboys

Let’s back up a second. When I launched Wells $treet at the end of June last year, one of my first stories investigated how sky-high beef prices were not trickling down to the individual cattle rancher.

Here are the facts from 2021:

Fact: As you were stocking up on steaks back then, cattle ranchers were losing money. “We generally need around $1,000 a calf to break even,” said rancher Brett Crosby, who runs about a thousand head of cattle in Wyoming and Montana. ”Calves were bringing in around $850 this last fall and spring [2020–2021].”

Fact: in 2015, the USDA said over 50% of the wholesale price of beef went to the farmer. That went down to 38%.

Fact: Covid hit the middleman hard — the meatpacking plant. This is where cows are slaughtered and processed for the consumer market. At least 25% of beef slaughter capacity was lost in the spring of 2020 due to Covid outbreaks.

Fact: Even with all that, meatpackers were having a great year.

Yes, even when meatpacking plants were shuttered, the four major packing companies made record profits. Beef cried fowl — I mean foul — accusing packers of manipulating the situation, perhaps illegally. Packers punched back, saying they’d slaughter more animals if they could, but they didn’t have enough workers.

Congress started asking questions and writing legislation. President Biden got all worked up, too.

So I thought I’d circle back and check on the facts as they stand in 2022.

Fact: Cattle ranchers are making money again. Cattle futures are trading anywhere from 16–20% higher than a year ago. However, some profits are being eaten up by higher hay prices as drought dries up rangeland across much of the country. (June saw record prices for alfalfa.)

Fact: Packing plant capacity is back up, and packer profit margins are back down, though still profitable. Margins have dropped from over $1,000 per animal to under $300, according to this chart from industry consultant Nevil Speer.

From Nevil Speer at Drovers.com.

Fact: Packers are still making a killing, even with lower margins. Tyson Foods, for example, says beef prices in the second quarter were 23% higher than a year ago (when they were already high). Update: Tyson Q3 earnings out this morning show that beef prices have dropped 1.2% from a year ago; the company blames “a challenging labor market and supply chain constraints,” not demand. Beef operating margins have more than doubled, to nearly 23%.

So. Wait. If the markets have fixed themselves — if everyone is making money along the beef supply chain — do we still need Congress getting involved?

Packers say no. Ranchers say yes. Either way, Congress is moving forward.

Let’s first follow up with a couple of the guys I spoke to last year.

The Rancher

Rancher Brett Crosby says he’s now selling animals for about $1,200 apiece — compared to last year’s $850 — above his break-even line. “Cattle prices have certainly come up,” he tells me with some relief.

He and others are actually selling more cattle than they did before Covid. You‘d think that adding beef to the supply chain would bring retail prices down, but demand appears to be keeping them high. “I’m not sure what’s driving beef demand,” he says, “because we’re producing more beef this year than last year.”

The Feedlot Owner

“Our slaughter pace has been the highest it’s been since the early ‘80s,” says Nebraska feedlot operator Lee Reichmuth, bearing out what Brett is seeing over in Wyoming. (Cattle go from the range to the feedlot to gain weight before heading to the meatpacker.)

A year ago Lee was up in arms over the number of cattle he had to keep feeding because packing facilities were so backed up. Now the backlog has virtually disappeared. “It’s been a nice turnaround for us.”

So Does Congress Need to Get Involved?

Despite the beef industry returning to something closer to normal, Congress is still considering two bills. Because… that’s what they do for a living.

One bill from Sen. Mike Rounds (R-SD) would create a special investigator within the USDA “dedicated to preventing and addressing anticompetitive practices in the meat and poultry industries and enforcing our nation’s antitrust laws.”

Another bill, led by Iowa Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley, aims to create more transparency in how cattle are purchased by forcing packing plants to buy half of all animals in cash.

A Very Brief Detour into the Financial Sausage-Making of Beef Prices — Skip to “Fewer Cattle Next Year” if You Don’t Care

Cash market prices for cattle are public information, and they’re used as a “floor price” by packing plants to create private contracts that take into consideration things like an animal’s superior genetics. Most private-contract prices are, um, private. Not public. And the vast majority of cattle are purchased privately. Very few are bought in cash.

Ranchers feel that private contracts leave them in the dark. Brett says he has to commit to selling animals on a Monday without knowing until Friday what he’ll get paid. He and others think that a law forcing packers to buy more animals on the cash market would provide price transparency.

But half the market in cash? That’s what the law proposes, but not even Brett thinks it needs to be that high. “As long as it’s regionally distributed [fairly], then I think you can get away with 15, 17, 20% and have it be statistically significant and reliable,” he tells me.

Perhaps more importantly, Sen. Grassley’s proposed legislation would create a library of past private contract prices — to further pull back the curtain on cattle prices. The pork industry already has a contract library, so why not beef?

But Does the Status Quo Need to Change?

A study out of Texas A&M by 17 agricultural economists disagrees with the need to change the current pricing system. They conclude that the use of private pricing formulas has been good for ranchers by “significantly” reducing transaction costs. They also believe that consolidation in the packing industry is mostly a positive. “While not necessarily a popular position,” they write, “most economic research confirms that the benefits to cattle producers [ranchers] due to economies of size in packing largely offset the costs associated with any market power exerted by packers.”

“There’s no doubt that consolidation has created efficiencies,” says Brett. “Whether that’s helped us or not is up for debate.”

However, the Texas A&M report suggests that a library of past contract prices could create more transparency and “help build confidence in the market.”

That’s a fair point. Ranchers don’t have much confidence in the market, and they certainly don’t trust packers. Would a price library change that? We may never know.

Both the pricing bill and the bill mandating a special investigator have made it out of committee in the Senate. Whether they make it to the floor for a full vote before the midterm elections and the end of the congressional term (and then if they go to the House, and then the President’s desk), well, who knows? Meantime, as I said, everyone is currently making money.

Except you, the consumer. And get ready to pay even more.

Beef: We can’t quit you. Yet. /Guido Mieth, Getty Images

Uh-Oh, Fewer Cattle Next Year — WHAT?

With the drought forcing ranchers to pay more to feed their animals, the nation’s cattle herd is starting to thin itself, because it’s no longer cost-effective to keep replacing cows once you send this season’s lot packing (pun!).

Feedlot owner Lee Reichmuth says the outlook is particularly bad in Texas and Oklahoma. “Many of the ranchers have run out of water and feed to a point where they have really increased liquidating their herds.” He, too, is buying fewer cattle.

Brett’s herd is 10% smaller than it was a year ago. “We’ve sold more mature cows through the first six months of this year than we have in any year since 2003,” he tells me.

This means consumer prices could stay high if Americans continue buying beef when there’s less of it.

Which is weird, right? “If beef prices are so high, that tells us we’re not creating enough beef,” says Brett, “which should create incentive for us to grow our herds.” Instead, they’re shrinking. “This isn’t a perfectly efficient market.”

Excuse me while I scratch my head in confusion.

Competition is Coming!

One last thing. In many remote regions of America where cattle are raised, there aren’t a lot of packing plants. It’s not profitable to truck your cattle 1,000 miles to a place that might pay more. You usually sell to the guys closest to you, and sometimes, there’s only one guy.

The good news is that more plants are being built. One new plant in Missouri is reportedly costing $450 million and will employ 1,300 people. Another is going up in Nebraska. Together they’ll be able to handle a million head of cattle a year. But the earliest they’ll open is 2024.

So here’s a prediction: The plants will come on line just as the nation’s cattle herd has declined. More facilities, fewer animals! The pendulum of pricing power will swing from packers to ranchers.

But that’s agriculture. Somebody wins, somebody loses (or doesn’t win as much), and their fortunes flip every few years. “We always have challenges,” says Lee. Yet somehow these people don’t quit. Food keeps showing up at the grocery store, and we manage to scrape together enough money to buy it. “I just hope we don’t have a recession that craters demand,” Brett said.

Hold that thought.

💰💰💰💰💰

Fun fact about fast food: Lee tells me that after an animal in the U.S. has been processed and turned into steaks and ground round, there’s leftover fatty meat that no one wants to buy. Or so you thought! Fast food chains buy that excess meat and blend it with lean beef that’s been imported from another country. A win-win for everyone! Who could’ve imagined that your basic burger is a symbol of international trade!

Share your thoughts by joining the conversation below or emailing jane@janewells.com. And share this article with anyone who eats food.

Cover image by debibishop/Getty Images