Robocalling Wasn’t Supposed to be Like This

The Inventor of the Call Center Wanted to Help People, Not Annoy Them

Welcome to Wells $treet. Do you know that your vehicle warranty is about to expire?

jk.

What I love about covering the world of business is that there’s always a fascinating backstory. Today we look at a brilliant inventor whose technology has been hijacked. His life story is filled with plot twists.

For more stories like this, support independent journalism by subscribing. Wells $treet is free, and it’s free of malware! I promise not to spam your inbox with fake warnings about your Amazon account being breached.

Technology can be so irritating.

Lately, I’ve been getting robotexts from candidates who don’t even live in my state. Here’s one from Sen. Marco Rubio.

Leave. Me. Alone.

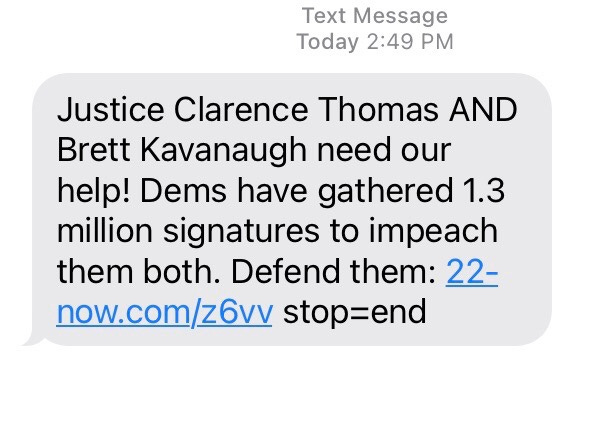

I don’t know why they’re targeting me or how they got my information, but twice a day I have to block some new text message coming in from who knows where. Like this one:

Robotexts are the latest obnoxious twist on robocalling, where tireless machines dial multiple random numbers, hoping you’ll pick up, and when you do, a prerecorded female voice tries to sell you a new auto warranty. A company called YouMail estimates there were over 32 billion robocalls through the first eight months of this year. If true, that's almost 100 calls per American, and...

Hold on. My phone’s ringing, again.

...

......

Grrrrrr. Does anyone actually buy one of these fake car warranties?

I wish there was a Robocop for robocallers.

Robocop with baseball. Why? Dunno/Mark Cunningham/Getty Images

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. Robodialing was originally created for emergency dispatching, according to Aleksander (Alek) Szlam, who is widely credited with inventing the call center technology. “I cringe at times,” he says of today’s robocalls. “It was never my intention.”

Alek’s backstory is a cross between Horatio Alger and Nikola Tesla. It’s the tale of an immigrant who fled persecution, landed in America and became a success through hard work and brilliance. It’s also a love story, as Alek married his sweetheart, a fellow immigrant, and together they built a company that would bring in revenues topping nine figures by 1999.

But then they lost it all. And the technology that was built to save lives became synonymous with one of life’s greatest nuisances.

From Polish Refugee to Ramblin’ Wreck from Georgia Tech

Alek was born in Klodzko, Poland, in 1951. His father’s first wife and two children were murdered by the Nazis while inside a synagogue. During the Holocaust, German occupiers forced his mother to live in a squalid Jewish ghetto for three years.

His family was finally allowed to leave Poland in 1969. The government barred them from taking anything, even passports. “You had nothing except a small card that said that you were actually an escapee,” he says. The family eventually made it to the U.S. a year later, and along the way he reconnected with Halina, a girl he knew from summer camp in Poland. She would eventually become his wife.

Alek’s family settled in Atlanta, where a mentor and Holocaust survivor convinced Georgia Tech to let the teenager from Poland enroll at the university on probation, as Alek had no high school diploma or SAT scores. He took to electrical engineering immediately, eventually earning a Master’s degree. He graduated and, after a series of “boring” jobs, accepted a position at a company that built PBX telephone systems.

That’s where he began his career as an inventor.

After a few years there, Alek was traveling to Wisconsin with his boss to visit a power company when he overheard a conversation about building an emergency dispatch system. The electricity company was trying to devise a more efficient way to contact maintenance crews during a power crisis in the winter. “People were dying because of no electricity,” he tells me.

Alek’s boss said their company didn’t know how to build such a system — they only designed and installed phone systems — but the young engineer from Poland asked if he could try. “My boss said, ‘Alek, it is impossible,’” he recalls. But he was not deterred. “When you say the word ‘impossible,’ forget it, it’s gonna be possible.”

Alek retreated to Georgia and worked in his garage to create and test an autodialing system that could recognize if someone answered a phone call, and then alert an operator to come on the line. He returned to Wisconsin with his working prototype, but it failed to perform.

Alek went home to perfect the prototype and circled back to Wisconsin.

And then something very strange happened.

“What in the world is this?”

Alek hooked up his improved system to an oscilloscope at the Wisconsin facility to test it for outgoing calls. Suddenly, “a phone next to me is ringing,” and the oscilloscope signaled that it was reading the incoming phone call… on this other phone that had nothing to do with what he was testing. He later discovered that the waves on the scope were indicating where the incoming call was coming from.

“I said, ‘What in the world is this?’” Alek began focusing on this new mystery. “I started playing,” he says, “and what I uncovered was that when [the phone was ringing], the phone number of that person calling was being transmitted. And I said, ‘How come nobody’s using this?’”

This was the beginning of caller ID and all the technology which followed. Nobody was using it back then because phones didn't have displays yet. (Remember when a telephone was merely a device with a rotary dial and a receiver? Man, I’m old!)

But Alek’s main goal was to perfect the outgoing call system, and he succeeded. One person could now do the work of four people, as computers would send out calls and signal if someone answered.

The Birth of the Call Center

Realizing that his system was adaptable to many applications, Alek formed Melita International, named after his sister, in the early '80s. He funded the startup with $6,000 in savings, and his wife — a biologist by profession — came on board to help manage the company.

They landed their first major call center sale. Fingerhut (remember them?) used the system to connect with existing customers, not to make unsolicited pitches. American Express used Alek’s technology to track down people who weren’t paying their credit card debt. Blood banks wanted the system to automate calls searching for donors. The Los Angeles Unified School District made a huge investment in Melita, using its “Sprintel” technology to notify parents of truant students. “We made quite a bit of money,” he remembers. “We never borrowed money.”

Alek during Melita's early days/Alek Szlam

It was the birth of the call center. “Our technology started selling at the speed of light,” Alek says, landing new accounts in dozens of countries. As sales grew, he invented more technologies, even writing a book on predictive dialing in 1996. “The harder I worked, the luckier I became.”

Alek ended up with 30 patents to his name in the U.S. alone. As Melita‘s sales hit a reported $100 million a year, he hoped to license his patents for millions more.

Then things went south. “It all disappeared.”

Pivoting to Telemarketing, and then to Bankruptcy

Alek says he was under pressure from some in Melita management to take the company public so they could sell some of their privately-held shares. He insists the company had plenty of cash in the bank. To have a successful initial public offering (IPO) — that is, to convince Wall Street that the stock would be a good investment — Melita first needed to show strong growth for several quarters.

Alek’s rivals were already starting to use call center technology to make unsolicited calls to strangers and market products. The belief by some at Melita was that this application would greatly increase revenues and take the company to the next level ahead of the IPO.

“This was a big struggle for me at first,” Alek says. He wanted the technology to help save lives or improve service to existing customers, not to “bother people” with advertising they didn’t ask for. But he acquiesced. “So we entered this market.”

He still regrets the decision.

Melita went public in 1997 and continued to grow. For a while.

______________________

______________________

______________________

Melita merged a company called Divine Inc. in 2001, and Alek was no longer CEO. He became Chief Strategy Officer, but he says he soon worried that the parent company was burning through cash too quickly. He tells me he warned the board of directors that the company would be insolvent by early 2003.

They ignored him.

Divine went bankrupt in 2003.

Alek Szlam lost much of his fortune as a result. “We could’ve built some of the best customer-interaction management software and hardware in the world,” he says wistfully. Over the years, he’s watched competitors sell their companies for hundreds of millions of dollars — or more — to companies like Facebook.

And while Alek has tried to start over with something new, he admits it’s been hard. He was involved in lawsuits over the bankruptcy for years. “I don’t really have trust for other people,” he says. “People say, ‘You should just regroup and start another company.’ It’s not so easy.”

These days he enjoys life with family, and he’s a longtime supporter and member of the Georgia Tech community. He’s also an avid cyclist and lover of classical music. Alek still provides consulting services, is active in Jewish causes, and he feels it’s important to give back to a community and a country that has given him so much.

But he also yearns to create something positive and valuable based on the work he’s already done. “There’s a lot of technology in these patents that no one has even touched yet,” he says. “I have so many ideas.”

☎️☎️☎️☎️☎️

This article has been updated with more details about the technology.

What do you think of Alek’s story? Please join the conversation below.

📧 jane@janewells.com.

✍️ Keep the comments coming!

📤 Share this Bulletin!