I love to look behind the headlines to follow the💰. You can learn a lot about history by finding out who funded it. If you like stories told from my warped financial perspective, please subscribe (it's free!) and spread the word.

Artwork by mikroman6/Getty Images

The Mayflower was the crypto of its day, a highly speculative investment fueled by #FOMO. But the 102 passengers (plus crew) who set sail from England in September, 1620, were not digital. They were not non-fungible.

They were very fungible.

However, they had something in common with certain cryptocurrencies.

While English investors in the Mayflower expected profits to go to the moon!, half the Pilgrims died within months, creating volatility in their “value.”

In the end, the investment did not pay off.

As we approach the 400th anniversary of the first Thanksgiving, celebrating the harvest of 1621, let’s follow the money behind the Mayflower.

“Embarkation of the Pilgrims” by 19th-century artist Robert Weir

WHO WERE THESE PEOPLE?

The folks we call the Pilgrims practiced a form of Puritanism which got them into trouble with King James I of England. They called themselves Separatists, and they made run-of-the-mill Puritans look pretty chill. While regular Puritans wanted to stay in the Church of England and clean it up, the Separatists wanted to just, um, separate, and do their own thing. The Separatists felt the Church, with James as its head, was still too Catholic.

James I (also VI, don’t ask), by John de Critz

King James feared if he allowed a bunch of subjects to ignore him as head of the church, others might start ignoring him as head of the kingdom.

In 1608, many of the Separatists fled to Holland to avoid persecution and prosecution. But as Nathaniel Philbrick writes in his fascinating book, Mayflower: A Story of Community, Courage, and War, Holland was also getting tired of the Separatists’ separatism. The religious group couldn’t get much work because they weren’t well liked, and by 1620 they were broke.

Several dozen Separatists decided to pool their meager resources, do a little fundraising, and head to the New World. They yearned for a place where they could be as anti-Catholic as they wanted, without any hassles.

Who would give these poverty-stricken radicals money?

THE HUNT FOR FUNDING

Nathaniel Philbrick writes that the Separatists first approached the Virginia Company, the same group that funded the trip to establish the colony in Jamestown in 1607.

But Jamestown was a disaster, and the Virginia Company had no money left to fund another trip.

Some Dutch investors expressed interest in financing the trip, but only if the Pilgrims would establish a Dutch colony.

Then an ironmonger from London named Thomas Weston showed up in Holland.

Weston represented a group of 70 investors called the London Merchant Adventurers. Philbrick describes Weston as “smooth talking,” an enterprising Englishman who saw huge moneymaking potential in the New World’s fishing, logging and fur trades.

I don’t have a painting of Weston, but he was this guy. Photo credit: Getty Images.

The Merchant Adventurers agreed to fund the trip by creating and buying shares in the venture. Each of the Separatists heading to the New World received one share, worth £10k, for free. The investors staying in London could buy in for about £20 apiece. All told, the Adventurers raised what might be worth $406,000 in today’s money.

HOW MUCH???

How did I arrive at that $406,000 figure, you ask? Well, 70 investors at £20 each is £1,400. I Googled, “What is a pound from 1620 worth today?” I discovered that the English Department at the University of Wyoming created a calculator which can compute the conversion rate going all the way back to the year 1264! Whaaaaaa???

If the calculator is accurate (and I have no reason to believe it’s not), the original Mayflower investment equals $406,000 in today’s dollars.

Weston and his fellow investors ignored the hard lessons learned at Jamestown. All they saw were the profits being made by ships coming back from the New World. They didn’t seem to realize that it’s one thing to take a boat across the ocean, load it up with a bunch of fish and furs, and sail back. It’s quite another to build a permanent settlement.

“They failed to calculate that even if the colonists engaged promptly in trading furs or catching fish, their initial task must be to build permanent dwellings and to feed themselves and a fair number of women and children,” writes Ruth McIntyre in Debts Hopeful and Desperate. “At the beginning they apparently underestimated the extent of their task and seem to have neglected consistently the necessary provision for the Plymouth colony.”

STRINGS ATTACHED

The trip kept getting delayed, and some investors started getting cold feet.

They demanded new terms and conditions to keep the trip funded.

First, the Merchant Adventurers wanted to send some of their own people along for the ride, because the Separatists couldn’t hunt, or fish, or log. So in addition to about 50 Separatists, the investors would put another 50 or so people on the ship, people who had actual skillz.

The two groups did not get along. In fact, the Separatists called the other folks “Strangers,” which tells you everything you need to know about their relationship.

The second condition the investors demanded was to put their people in charge of booking a ship and buying provisions… and their people screwed it up. A universally disliked guy named Christopher Martin was supposed to buy food and beer and tools, but he squandered the money. “Smooth-talking” Thomas Weston was supposed to secure a ship, but he diddled so long that the Separatists went ahead and booked another ship, the Speedwell.

The Speedwell ended up springing leaks, and it had other problems, and, well, the whole thing was turning into a sh*t show.

By the time Thomas Weston secured the Mayflower, the passengers were already running low on provisions, and they hadn’t. even. left. England.

The third string attached to the funding nearly snapped the entire agreement. Thomas Weston (that guy again!) told the Separatists that if they wanted the money, they had to agree to new terms of repayment.

The original terms called for the soon-to-be colonists to work four days a week for seven years in the New World procuring goods to pay back the investors. They would also own their own homes and keep 100% of any profits they’d make selling them.

The new terms called for the Pilgrims to work six days a week for seven years for the investors, and split the profits if they ever sold their homes.

A guy named Robert Cushman, representing the Separatists, agreed to these new terms, but the rest of the group was outraged, calling it a form of extortion “fitter for thieves and bondslaves than honest men.”

One Separatist leader, 30-year-old William Bradford, kept a record of everything, and even he started to have second thoughts.

“I think there is not a man here who would pay anything, if he had his money in his purse again,” Bradford wrote in his diary. “We depended on Mr. Weston alone, and upon such means as he would procure; and when we had in hand another project with the Dutchmen, we broke it off… “

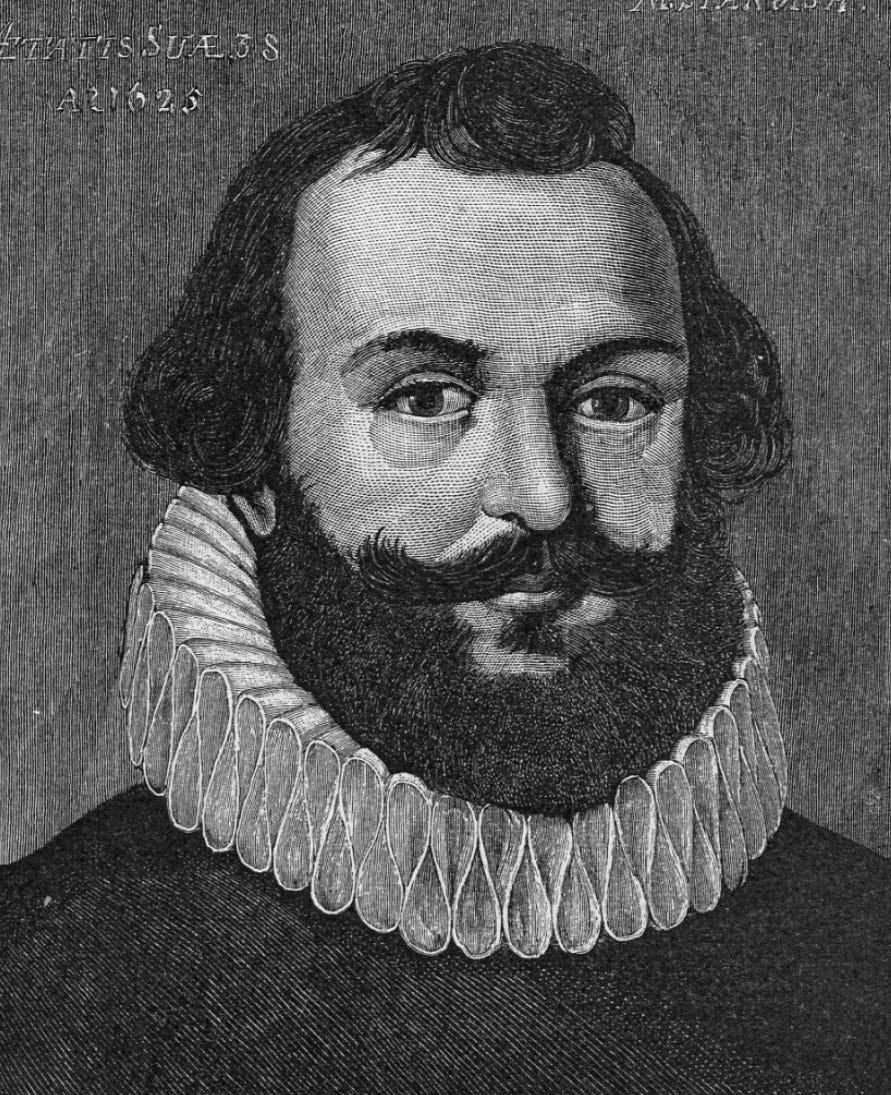

William Bradford, wishing he’d gone Dutch.

Well, anywhooooo.

In early September, 1620, all 102 passengers, and a crew of about 30 plus two dogs, set sail aboard the Mayflower from Plymouth, England. They were headed for northern Virginia. Half of the passengers were Separatists, and half were “Strangers.”

Two months later, they saw land.

It was the the wrong land.

The ship had gotten off course (of course) and ended up in Cape Cod, in early November, during the worst winter in local memory.

The newcomers started dying on a daily basis.

Those who did survive didn’t have much luck at fishing, or hunting, or growing anything they could trade for furs.

The investors in England waited.

And waited.

The Mayflower returned to England in April 1621 with her captain and surviving crew, carrying absolutely zero pelts, codfish or anything else of value.

The investors were ticked.

They sent over another ship called The Fortune a few months later, carrying 37 people who didn’t bring much food with them. (Great! We’re already starving here!) The Fortune also brought over a stern letter from, wait for it, Thomas Weston, who complained about the Pilgrims’ lack of progress in turning a profit.

“I know your weakness was the cause of it,” Weston wrote, “and I believe more weakness of judgment than weakness of hands.“

William Bradford blew a Puritanical gasket. So many of his fellow colonists had already died, including his wife, who drowned after slipping (or intentionally stepping) off the Mayflower one day as it sat in the harbor.

“[O]ur arms and legs can tell us to this day that we were not negligent!” Bradford shot back. ”But it pleased God to visit us then with death daily, and with a disease so disastrous that the living were scarcely able to bury the dead, and the healthy not in any measure to tend the sick.”

Still, Bradford and his hearty band of survivors knew they had a debt to pay, and so they loaded up the Fortune with beaver skins, sassafras, and oak clapboards worth about £500 – or $145k in today’s dollars – making a serious dent in their debt.

Then the Fortune met with misfortune.

A French privateer seized the ship just before she got to England and took everything. This would not be the first time a ship laden with goods sent by the Pilgrims was captured by pirates.

Meantime, Thomas Weston sent another ship over to the New World with about 60 people aboard to start a different colony, to compete with the Pilgrims.

That guy.

Weston puts the turkey in Thanksgiving.

SO WHAT FINALLY HAPPENED?

Ok, let’s wrap this up and get to the pumpkin pie.

For the next few years, the Pilgrims continued to ask their English investors for more money, provisions, tools and other stuff. The total investment may have reached £7,000 ($2 million today).

By 1626, both sides agreed to settle. The investors sold their shares to the surviving colonists for £1,800, an ROI worse than the decision to buy Bitcoin at $68k.

All good, right?

Wellllll, the Pilgrims then engaged in trade with other merchants back in England. Over the next couple of decades, even as Plymouth Colony became more prosperous, they could never turn a profit. Nathaniel Philbrick writes that according to Bradford’s own calculations, “between 1631 and 1636, they shipped £10,000 in beaver and otter pelts [almost $3 million today], yet saw no significant reduction in their debt of approximately £6,000 [$1.74 million].”

William Bradford suspected he was being defrauded by his intermediary in London, but Philbrick says Bradford deserves some of the blame. He never had a knack for numbers.

It wasn’t until 1648, nearly 30 years after leaving England, that the Pilgrims finally paid off all of their debts, selling some of their land to make it happen.

The original Plymouth Colony languished as new settlements popped up and thrived. “And thus was this poor church left,” Bradford wrote, “like an ancient mother grown old and forsaken of her children.”

William Bradford lived to be 67 years old and died in May, 1657. He was buried at Plymouth Colony.

Thomas Weston ended up in the New World, where he was arrested a few times, before returning to England.

He died of the plague.

WAIT, WHAT ABOUT THANKSGIVING?

Oh, that.

There’s no documentation of anyone eating turkey at the first Thanksgiving in the fall of 1621. We know that the surviving Pilgrims celebrated a bountiful harvest, and that they were joined by Massasoit, the local tribal leader who helped them survive.

Massasoit brought so many members of his people to the harvest festival that they outnumbered the Pilgrims two to one. He also brought five deer to eat, and everybody ate drank and played games for a few days.

The two groups remained friends. For a while. Then things changed.

But that’s a story for another time.

Massasoit’s people saved the Pilgrims, and they protected each other.

HEAR THE THANKSGIVING STORY TOLD A NEW WAY

Back in 2018, as the 400th anniversary of these events approached, I wrote a scripted podcast re-enacting the story of the Mayflower as if modern media existed in the early 17th century. Teenager Priscilla Mullins livestreams the trip across the ocean, whining, “Worst trip ever!” Myles Standish cannot get the hang of Instagram. Native talk radio hosts debate whether to kill the newcomers. It’s the first season of what I named ”Top Story Tonight!,” and the cast includes everyone from Michael Horse of “Twin Peaks” to CNBC’s Guy Adami. (Other seasons include Christmas and Easter, and I’m currently working on Cleopatra, the original Kim Kardashian.)

The podcast brings the story alive in a fun new way, and I hope you’ll give it a listen. Here are links to all six episodes, each around 20 minutes long, in case you want to binge some audio on a holiday roadtrip!

Episode one, “Voyage of the Damned”: “Ye Olde Nightly News” reports that the Separatists are leaving Holland. As the religious group is forced to accept new passengers, a near-mutiny breaks out. Then the Mayflower finally arrives in the New World, where a local morning show host cheerily reports it’s going to be the coldest winter on record.

Episode two, “A Bad Rap”: There’s “mayhem on the Mayflower,” as passengers bicker over how to govern themselves. The “Mayflower Compact” is a forerunner of things to come in America, and it’s so historic that everyone on the ship breaks out in a really bad Broadway-style hip hop rap to celebrate.

Episode three, “Pilgrims’ Progress”: William Bradford reports on his “Plymouth Podcast” that things are not going well. Arrows are flying. Food is scarce. Time for a pledge drive.

Episode four, “Indigenous Indignation”: The newcomers, led by Myles Standish, make first contact with the locals. Standish freaks out trying to capture the whole thing on Instagram.

Myles Standish was in charge of defending the Pilgrims.

Episode five, “A Love Story”: In a break from the historical record, we use this opportunity to turn Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem “The Courtship of Myles Standish” into a version of “The Bachelorette.”

Episode six, “Giving Thanks?”: After a helluva year, the Pilgrims and their local allies prevail over other tribes and make peace and, in the fall of 1621, a pre-cog Oprah Winfrey hosts her first Thanksgiving special. However, the surprise gift she’s placed under every seat in the audience turns out to be a very bad idea.

Next month, just in time for Christmas, I’ll follow the money behind King Herod and Cleopatra. Both were fabulously rich and they hated each other, but in a few decades, they’d be overshadowed by the story of a baby born in a barn in Bethlehem.