Vinyl and Victrola — Gen Z Plays New Music on an Old Format

Welcome to Wells $treet, where I follow the money down unusual alleyways. What I find can amaze me, amuse me, or enrage me. Today’s story amazes me, because it’s the story of an iconic brand that disappeared long ago. Now it’s back and thriving, thanks in part to the pandemic.

If you enjoy these stories, subscribe, and click on this link for an instant email to forward to like-minded friends and family. (See how easy I made that?)

💰💰💰💰💰

In a world filling up with NFTs, most of us still like to buy something we can hold in our hands. Even as someone is reportedly spending $450,000 to be Snoop’s neighbor in the metaverse, good old “analog” investments are still attractive.

Vinyl is back, baby. It never actually went away, but it’s come out of the shadows and back into the mainstream music scene. Adele pressed a half million vinyl copies of her album “30,” officially endorsing this new (old) format.

But vinyl is also more difficult to find and expensive to press right now. Rising oil prices not only affect the physical cost of vinyl, which is petroleum-based, but it increases the cost of transportation, especially compared with digital streaming. Plus, there are very few large pressing plants left. Two years ago a fire destroyed one of only two places in the world providing the lacquers needed to make master discs.

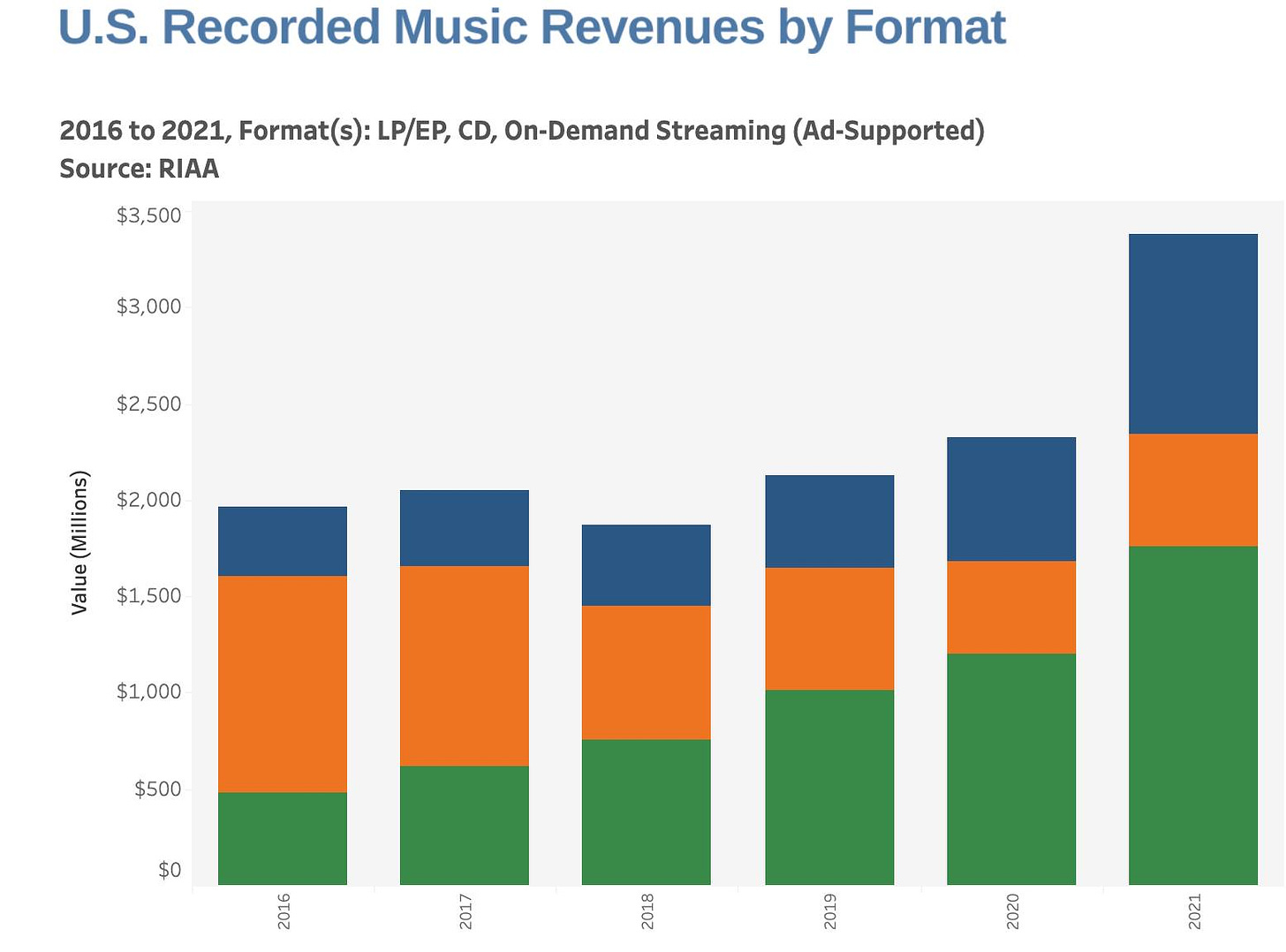

Still, demand is high. As concerts shut down in 2020, people started buying turntables. Vinyl outsold CDs in 2021, comprising more than one in three albums sold. A survey by MRC Data, which tracks music sales, found that Gen Z consumers bought more physical records than Millennials did last year.

Sales of vinyl albums (blue) vs. CDs (orange) vs. streaming (green)/RIAA

“People just like to touch things,” says Mike Mandel, a former distributor who sold tens of thousands of records in the '90s, specializing in underground dance music. Now he sells all kinds of old vinyl recordings on Discogs, an online marketplace for music buyers and sellers. Physical records have a warmer sound than digital recordings, something Mike likens to magic. “There’s these grooves in a record on this piece of vinyl, and music happens,” he says with a smile. “It’s like sorcery!”

Mike says more established musicians are attracted to vinyl because they can make more money selling records than streaming on Spotify, “unless you have a million streams a day.”

And here’s something else: When consumers buy an album, they tend to listen to the whole thing, or at least one side. And they really remember the music.

I grew up listening to vinyl records, and even now, when I hear a Cat Stevens song from “Tea for the Tillerman,” I anticipate which song will play next, based on memory — “Wild World” should be followed by “Sad Lisa,” right? (Am I the only one whose memory kicks in like this?)

In the midst of this, an old brand is rising from obscurity.

RCA Victor's Nipper the dog/Blank Archives/Getty Images

To Everything, Turn, Turn, Turn...

Victrola is making a comeback with new turntable record players for a new generation (but without the dog logo; apparently there are some rights issues).

“We will eclipse over $100 million in sales this year,” says Victrola CEO Scott Hagen from the company’s headquarters in Denver. Over one million units were sold in 2021, and Victrola now commands nearly half the record player/turntable market.

Scott says the company’s fastest-growing segment of buyers is between 18 and 36 years old, split almost evenly between men and women. “We think it has a lot to do with the communal experience that generation is looking for in entertainment.”

The company is producing new portable, battery-powered “suitcase” record players in bold colors that double as Bluetooth-connected speakers, with some models selling for under $100. The subwoofer is built in, and the units have been redesigned so that you can blast the bass without bumping the album on the turntable.

But where has Victrola been all this time? The brand dominated the “talking machine” industry for half a century after being founded in 1901 in Camden, New Jersey. It became part of RCA. Then television came along, and everyone figured the TV would become the home entertainment center. Victrola faded away.

For decades the brand sat dormant in someone’s portfolio of ... dormant brands. Then a company called Innovative Technologies bought it in 2015. A private equity firm out of Philadelphia called RAF came in as a partner to help relaunch Victrola.

Scott says they chose Denver as headquarters after researching 19 cities, including Nashville and Austin. “Do you know that there’s more music per capita in Denver than there is in any other city in the U.S.?” Scott asks me. No, I did not. I’ll take his word for it.

Overcoming the Turntable “Stigma”

For all the growth that the company is enjoying, veteran record collectors aren’t quite on board with the new Victrola yet. “I immediately think of the RCA logo with the dog,” says Mike Mandel. He doesn’t own one. (A Victrola, that is; he may own a dog.)

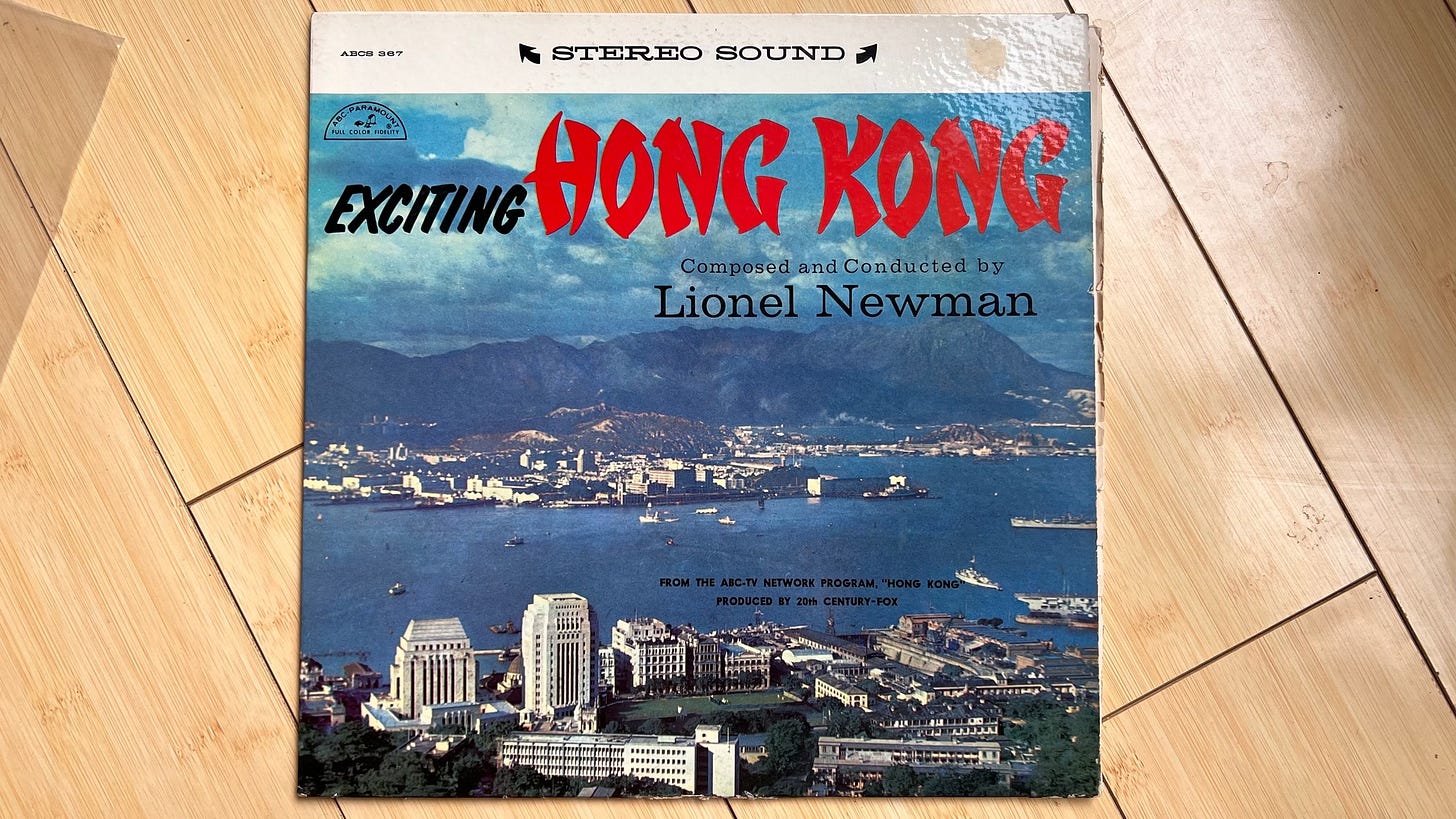

Record collector Andrew Coffey of Chicago is more a fan of the old Victrolas. “My parents had a record player,” he says. Growing up he listened to albums from “West Side Story” and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” He still loves buying old records for their art and history. “It’s like a snapshot of what people were listening to.” Here are a couple of Andrew’s LPs:

One day back in the ‘80s, Andrew says his brother came home from France with a Victrola, “one with a big horn.” Andrew decided he needed one, too.

He found it a decade later in Vietnam. It’s a crazy story.

Andrew’s big find!

Andrew says he went to Vietnam to scour antique shops in Ho Chi Minh City. He got around on a pair of rollerblades while being pulled by a local guide on a bike (a “cyclo”).

Andrew being “transported” via rollerblades and ”cyclo.”

“We came upon this guy,” Andrew recalls, “and he was cleaning this beautiful Victrola that the French had brought over there in the ‘20s.” The guy wanted $30. Andrew gave him $25. "I would’ve paid $50.” And then what? “I sat on the back of the bike with the Victrola and went back to the hotel.”

He still has the phonograph, and he still plays records on it. But does Andrew have any interest in buying a new Victrola? Not really.

Scott Hagen, Victrola’s CEO, gets that.

“It’s an audience we respect heavily,” he says of collectors. “It’s an audience that’s actually kept the format alive for so many years.” He says Victrola is trying to overcome an image problem plaguing the entire turntable industry that’s caused by a lack of investment in innovation.

“There’s always been this stigma that either you get a really cheap, not great-sounding, not great-performing suitcase record player,” Scott says, “or you have to have massive complexity and cost in your life to get a record to sound good.”

Victrola is trying to hit the middle with something that’s easy to use, affordable, and sounds great.

Scott is leaning on his experience working at Best Buy for 18 years, during a time when that chain was fighting off potential destruction by Amazon. “One thing I think my time at Best Buy has done for me — that really puts Victrola at an advantage — is it got me so close to the consumer.”

Victrola is not only focusing on selling record players to consumers, but also creating new record collectors. They’ve started a subscription service, kind of like the old Columbia Record Club. “To me that was a really great way to experience and learn new music,” Scott says. Consumers can also buy records right on the Victrola website, both new and old, from the Beatles to Billie Eilish.

And yes, as analog as the product is, Victrola is preparing for a potential future in the metaverse, where it might help create virtual concerts.

The Long and Winding Road

The lack of new vinyl is holding back growth, though. With few pressing plants, wait times are getting longer for new recordings. Billboard reports the estimated global capacity for pressing vinyl records is currently around 160 million albums a year, but market demand is somewhere between 320 million and 400 million.

Of course, too much demand is a good problem, and Victrola hopes supply will ramp up. Scott Hagen says the company wants to recapture that old experience of families hanging out listening to records. “I made my son sit down and listen to the Paul Simon ‘Graceland’ album from beginning to end,” he says. They’d recently watched a documentary about the making of the album during the apartheid era of South Africa. “We got to talk about it, so I got to share a memory with him, but at the same time, I was creating a new memory.”

The power of communal listening is something Andrew Coffey experienced firsthand during that crazy trip to Vietnam 30 years ago. The man he bought the Victrola from gave him an album of old Vietnamese opera music. When he returned to his hotel, he decided to play the record on his new purchase. The Victrola had no volume control, and the music blasted through the lobby. “Out of the corner of my eye, I could see all these old people looking out of the kitchen.” They were mesmerized. Someone came up to him and said, “They haven’t heard this music in years.” Good luck hearing that on Spotify.

🎵🎵🎵🎵🎵🎵

You know what I miss most about records? Album art and liner notes. What was your first record? Mine was a 45 of Arlo Guthrie's “The City of New Orleans.” Send me some of your album art, I will post it on social media!

One more time:

➡️ Follow me on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram!

📫 Email jane@janewells.com.

👍 Like this story and share it.

🫶🏽 For the love of God, subscribe.