Images From The Eclipse

I made a late decision to drive 300 miles to see the total eclipse. It was the right call.

In the days before the April 8 solar eclipse, I couldn’t make up my mind whether to travel north from New York City to see the full total eclipse. New York would get 90% of the full effect. Everything I read warned that in the zone where there was 100% totality there would be mobs of people and horrific traffic getting there and back. And for what? To witness two plus minutes of the sun blocked by the moon? I was dubious.

Then last Friday, I read Jane Wells's Substack newsletter [Jane Wells from Wells $treet] saying persuasively that it was worth the effort to experience the full effect. I know Jane. Jane is a friend of mine. I believe Jane. So, I emailed her.

"If I drive 5+ hours, I can reach the 100% zone. Do it? 95% won't cut it?" I asked.

Jane replied, "It's not the same. When things go dark and suddenly, POP, the corona appears and the air gets cold ... wow."

That got me leaning toward going to upstate New York north of Albany, the closest drive for me.

But, come Sunday, I wobbled back toward staying put. Inertia was reclaiming me as it is wont to do. Then I happened to read an article in the Washington Post that quoted various people who said what Jane said: don't settle for anything less than 100%. One of those cited was Annie Dillard who had written in 1982 about a solar eclipse she drove 500 miles across Washington State to see.

"A partial eclipse is very interesting. It bears almost no relation to a total eclipse," Dillard wrote. "Seeing a partial eclipse bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him, or as flying an airplane does to falling out of an airplane. Although one precedes the other, it in no way prepares you for it."

I left Manhattan at 5:30 a.m. on Monday, Eclipse Day. My destination was Essex, New York on the western shore of Lake Champlain. It took five hours but, by then, clouds were drifting in from the west, threatening to contaminate the view. In Essex, there was a small ferry to the Vermont side of the lake just a little south of Burlington. The skies over Vermont looked bluer, clearer. That was where I would go.

Below are photos I took with my iphone except for one which is from NASA).

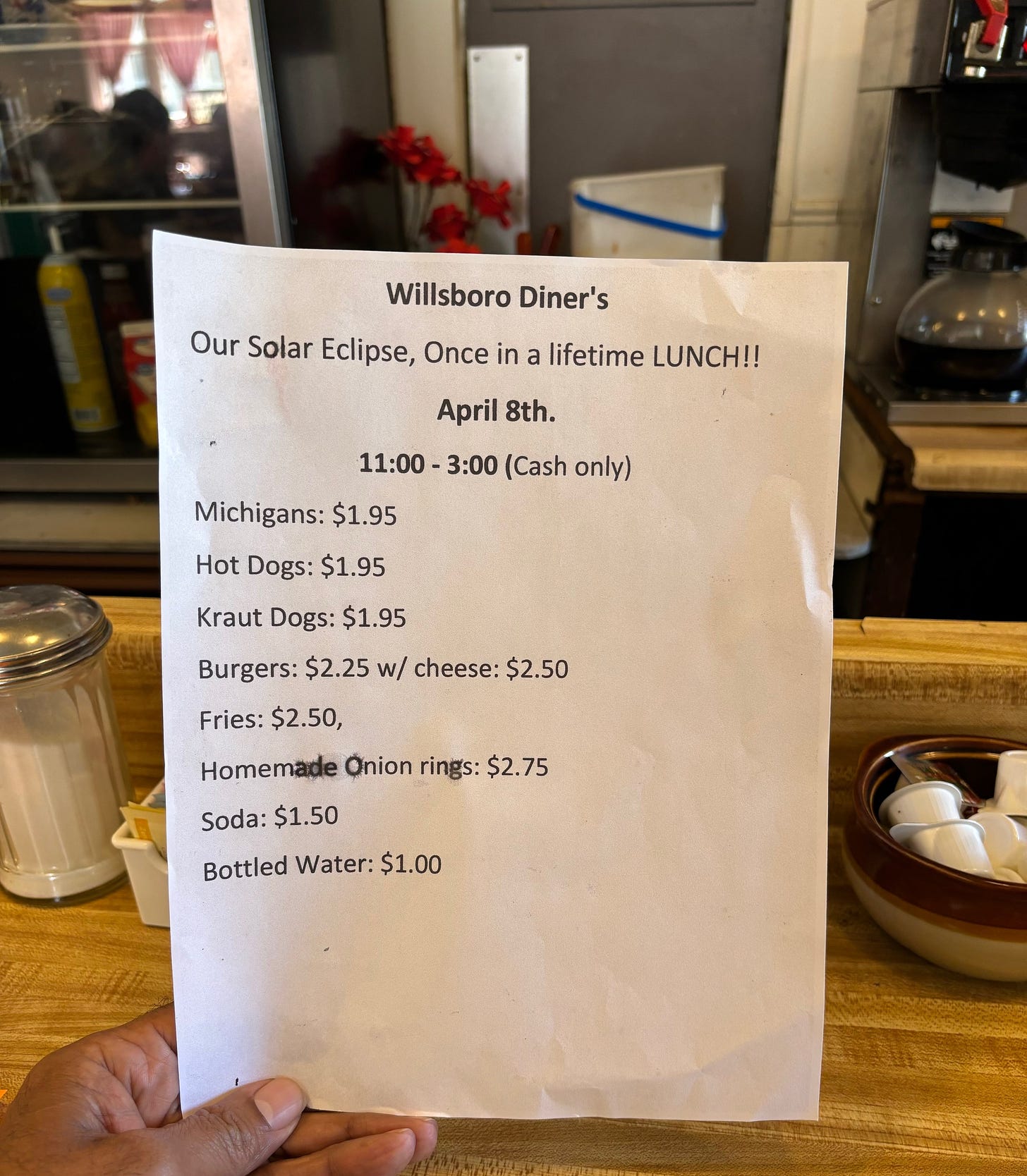

The Willsboro Diner, in the town of Willsboro, just north of Essex, was offering a special “once in a lifetime” eclipse lunch menu.

Surprisingly, there were no crowds in Willsboro or Essex.

When the sky began to cloud up, some people caught the ferry from Essex to Vermont where the skies were bluer. Vermont was only two or three miles east but the idea was to get ahead of the clouds. A man who was with his young son said he had come from Lake Placid, which is northwest of Essex. He said conditions there were deteriorating. Thick clouds were moving in, so they left. On the ferry, I spoke to a man who said he'd driven the day before from Princeton, New Jersey to Niagara Falls - over 400 miles - but when things looked bad there Monday morning, he drove the 360 miles to Essex.

The ferry arrived just before 2 p.m. I headed east without a destination. Alongside a two-lane road, I saw a car parked on the side and a woman sitting in a lawn chair sitting beside it on the edge of a vast field.

The woman turned out to be Eleanor, a retired teacher, who had driven up that morning from her home in western Massachusetts..

The eclipse began at 2:14 p.m. Eastern time as the moon began its slow movement in front of the sun from the lower right. On the other side of the road, two kids laughed as they tossed a football in their yard, seemingly oblivious to what was happening.

Everything began to take on a weird sepia tone about an hour into the eclipse. It was a little like normal gloaming, but not. The ambient light was tinged in a brownish hue I had never seen before.

These four images above depict the darkening as the eclipse approached totality. The temperature fell slowly at first, then quickly.

Total eclipse occurred at 3:26 p.m. This iphone image fails the capture the majestic beauty of that moment when all but a sliver of the sun disappeared behind the black disc that was the moon. The temperature fell and we were enveloped in darkness. I had read that birds fall silent during totality, but I heard just the opposite. Birds began squawking madly.

Peering into the sky, now without the protective lens, I stared in awe at the orb of the moon and around its circumference the glowing solar corona.

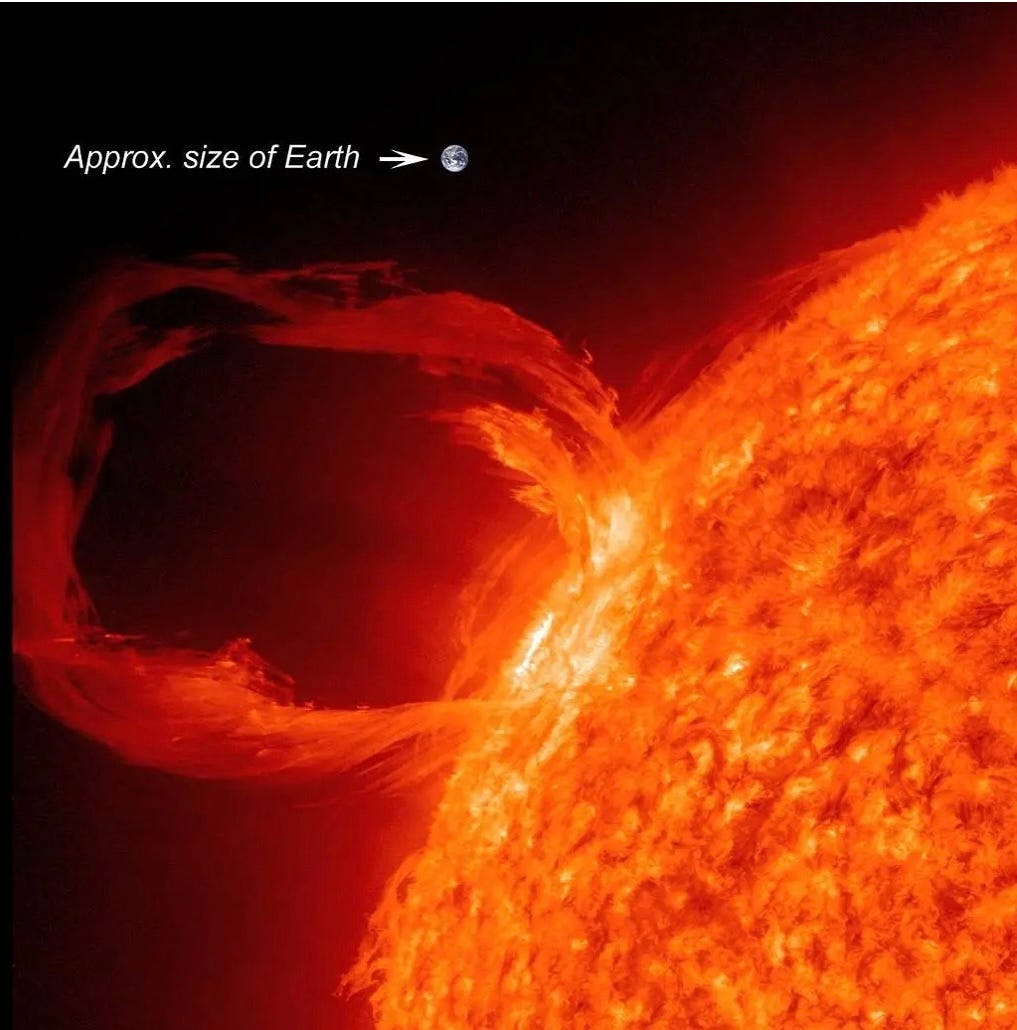

In the bottom left - the 7 o-clock position on a clock - I saw a bright red dot. It was mesmerizing but also bewildering. What was it? Was I imagining it? Only later would I learn that that dot was an extraordinarily rare solar prominence, an huge glowing loop of electrically charged hydrogen and helium called plasma, swirling away from the sun but attached to it.

Solar prominence, photo credit: NASA

In less than three minutes, totality was over. I wanted to cling to it. But already the experience was receding into the past, slipping away. It was becoming a memory.

.