Overcoming Shame as a White Collar Ex-Con

Would you hire a professional with a record of theft?

Quick note: It’s been four years since lockdown. When someone asks, “What did you do during Covid?” I answer, “I wrote this really weird podcast.”

We’re coming up on Easter, and in the spirit of “The Good News” — with a dash of humor! — I submit to you the podcast I wrote during Covid, “Top Story Tonight: Jesus!” It creatively retells the last week of Jesus’ life as though modern media and social media existed 2,000 years ago. For example, Peter and John are interviewed by someone who sounds a lot like Joe Rogan, while Mary Magdalene debates the high priest Caiaphas on an ancient version of “Rachel Maddow.” It even has commercials from 30 A.D., like this one voiced by Fox Sports’ Petros Papadakis.

I interweave the production with interviews of *real* biblical experts to discuss what we know about Jesus, and what we have to take on faith.

During Covid I raised money on Kickstarter to pay for actors and music and other production elements, and I can’t believe how many people supported this crazy project. If you’re one of them, thank you.

🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸

And now today’s topic. Sticking with the Bible, think of the following as a 21st century story of The Prodigal Son. (You can also just skip to the bottom for the section called “How to Survive Prison.”)

Last week, 31-year-old Amit Patel was sentenced to over six years in prison for stealing $22 million from the Jacksonville Jaguars when he worked in the team’s finance department. The Athletic reports that like many bumbling first-time criminals, Amit spent some of the stolen cash stupidly — a $95,000 watch, plus $47,000 on a Tiger Woods putter, and a lot of gambling. You get the picture.

During his sentencing, Amit told the court, “I stand before you embarrassed, ashamed and disappointed by my actions.”

He’s done the crime. He’ll do the time.

But what happens when Amit Patel walks out of prison? Will anyone hire him? Can he become a productive member of society? Sure, he might get a menial job paying minimum wage, but would that be the best use of his (reformed) talents? Maybe there’s a more beneficial way to re-enter society beyond working as a burger-flipper (not that there’s anything wrong with that!).

Good luck.

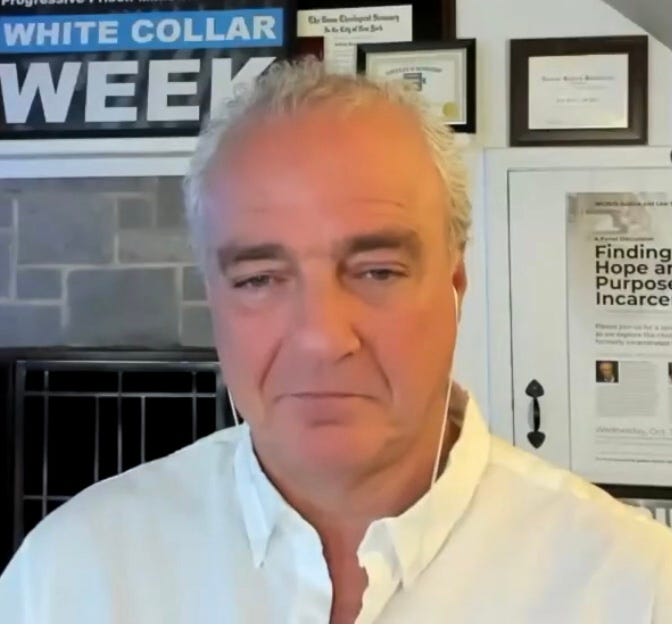

There’s a growing number of programs to help ex-felons transition into employment, but most of those initiatives find jobs for so-called “blue-collar” men and women who’ve turned their lives around. Almost no one wants to help privileged professionals. “You had your chance and you blew it,” says Mike Neubig, a former CEO of an education company. He pleaded guilty in 2020 to lying to investors.

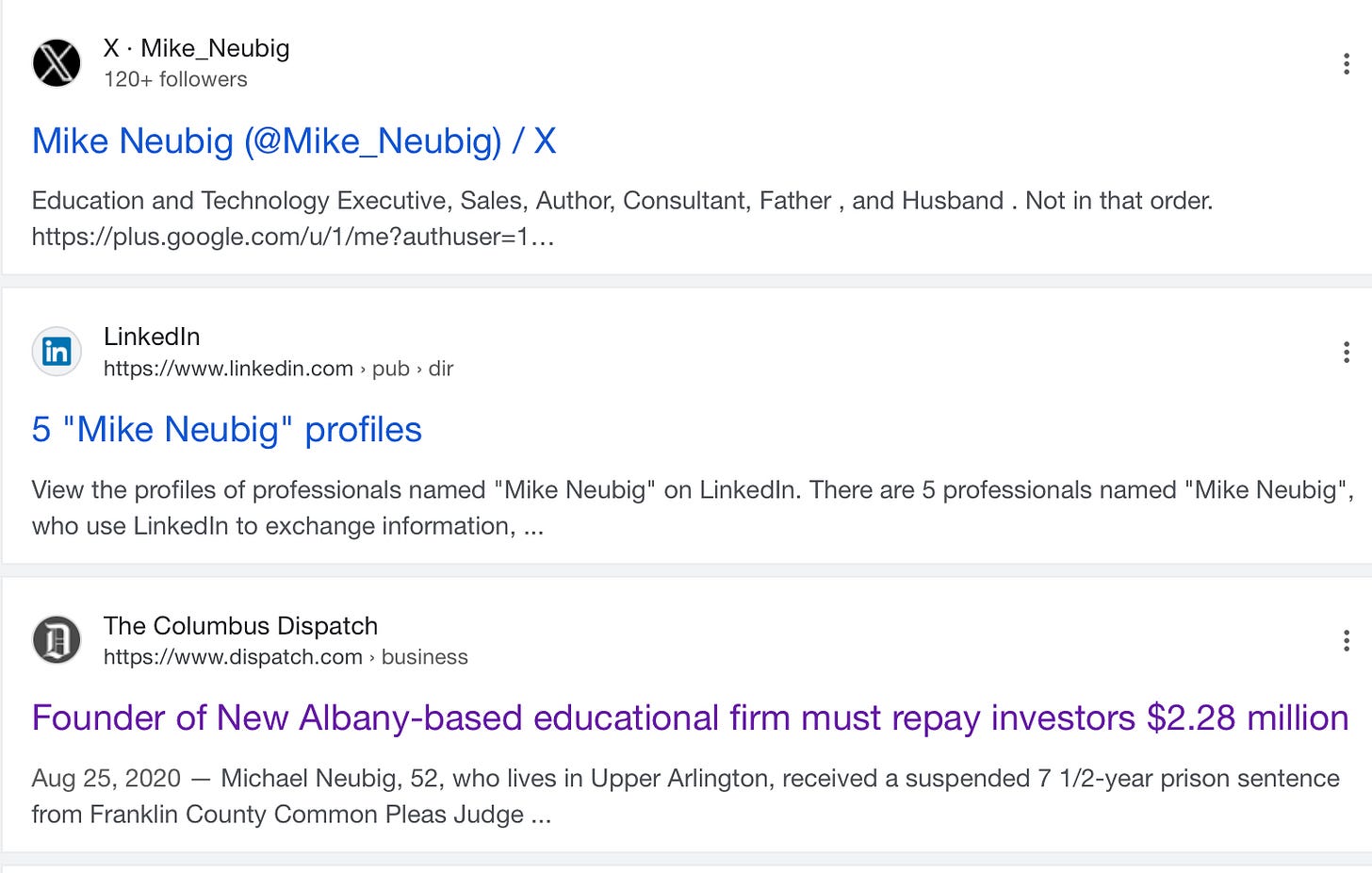

If you Google “Mike Neubig,” the third item that shows up after his X account and LinkedIn profile is a story with the headline “Founder of New Albany-based educational firm must repay investors $2.28 million” (see below). In addition to the multi-million dollar fine, Neubig received a suspended 7-year prison sentence, and he was ordered to spend a few holidays in jail.

His life was ruined.

About three items below the news story, you’ll find a YouTube interview with Mike from 2021.

I did the interview.

I interviewed Mike for a story called “Will No One Hire This Man?” It focused on the dilemma faced by white collar ex-felons. They’re usually smart and well-educated. They’ve had opportunities. It’s also very hard to forgive them. Society seems more open to providing second chances for ex-felons who grew up in poverty. There’s zero sympathy for people like Elizabeth Holmes or Sam Bankman-Fried.

Back when we spoke in 2021 after his conviction, Mike was struggling to keep a job. He’d been fired twice after managers discovered his record. “Once they know, they don’t want anything to do with me,” he said. He told me it would be tough to get a job even as a janitor. “Can you trust the white collar ex-felon late at night alone in an office?”

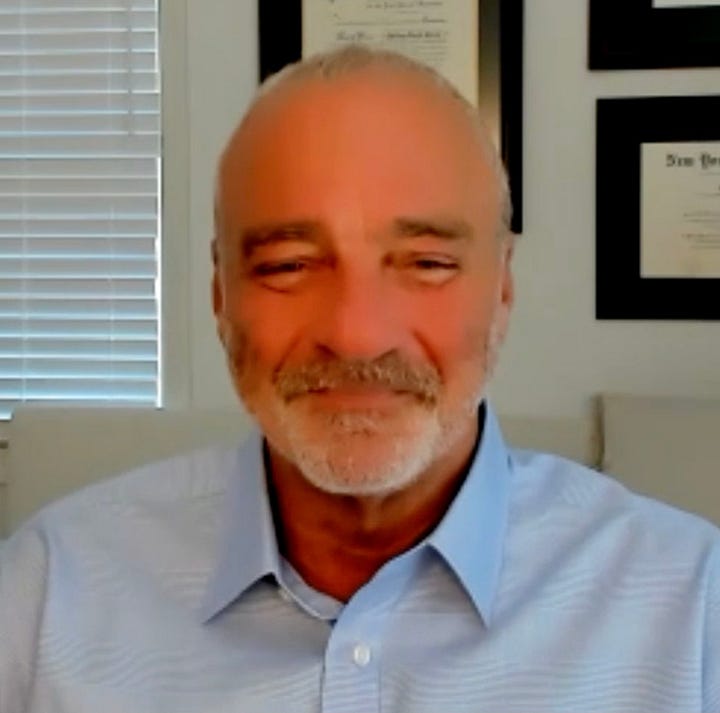

In that same article I spoke with two other professionals who’d actually gone to prison: Jeff Grant and Scott London.

Jeff’s story was really crazy. He was a successful lawyer who became addicted to painkillers and started stealing money from clients. He fraudulently applied for a federal loan after 9/11. Then as law enforcement began closing in, he tried to kill himself. But with the help of friends and family, Jeff got into recovery. He was clean and sober by the time he went to prison, and he served a year in a correctional facility where he was the only lawyer among “1,500 drug dealers.”

After his release, Jeff went to seminary, became a drug counselor, and started Progressive Prison Ministries to specifically provide emotional and spiritual support to white collar criminals and their families. “We give them hope and some guidance on how to move forward,” Jeff explained. The group holds weekly Zoom meetings.

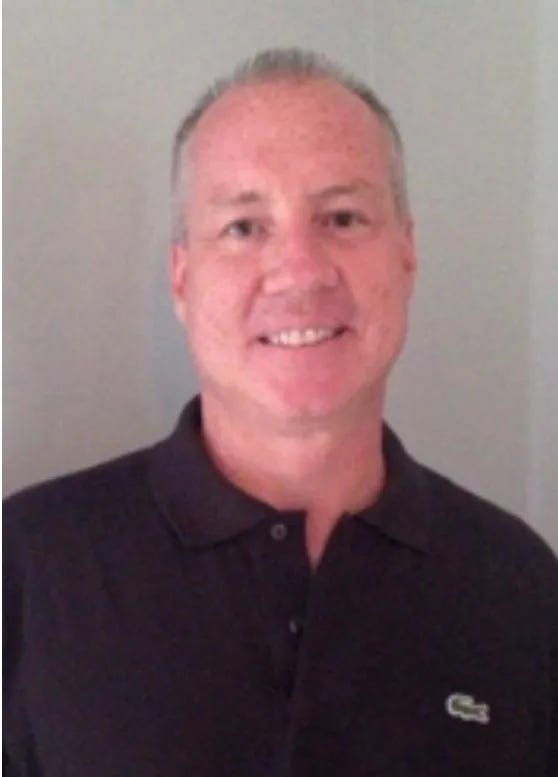

Meantime, Scott London’s story was one I covered for CNBC. He was a senior partner in the L.A. office of auditor KPMG, and he went to prison in 2014 for providing a friend with insider information on a couple of companies. Scott spent the first 30 days in prison locked up in solitary — a wild story he recounts in the original article.

Scott’s case was different. He went against the advice of his attorney and pleaded guilty. In fact, he confessed to everything the minute the FBI showed up at his door. His mea culpa may have helped, because when he was released from custody, Scott immediately got a job from a friend who ran a tech company. He was soon promoted to chief operating officer. These days he works as a consultant to wineries.

His life turned out okay.

It’s been a longer road for Jeff and Mike, and I recently reached out to both of them to see how they’re doing.

“I’m no longer ashamed.”

When I first met Mike Neubig, he was tense, desperate and frustrated. Nearly three years later, he’s relaxed and confident.

“I’ve changed a ton, and I’m no longer ashamed,” he tells me. “I’ve come to grips with who I was at that time and what I have to offer now, and it’s a lot easier to talk about it.”

Mike developed “tricks of the trade” in seeking work and telling his story. He usually waits until the second interview to reveal his record, and he does so without looking down or “stuttering, not sure how to talk about it.”

His now makes a steady, decent salary. After we originally spoke, Mike got a job working at an educational non-profit, and he was eventually promoted to the company’s senior partnership development director. In 2023, he started working with an education technology company in the United Kingdom that wants to move into the U.S. He doesn’t blab to co-workers about his past, but he doesn’t cover it up, either.

Mike tells me he continues to make payments toward his court-ordered restitution.

He’s also filing paperwork to start his own nonprofit to help professionals like himself who are dealing with a conviction. He wants to coach them on how to find work, and he also hopes to set up a platform for job listings. “The message is one of hope and recovery,” he says.

“Zero” Recidivism

Jeff Grant, meantime, is hardly recognizable from the man I first interviewed in 2021. He’s tanned and trim, having moved to Florida. “I’m 21 years sober,” he tells me.

Jeff managed to win back his law license. His practice, Grant Law, specializes in representing white collar felons who are dealing with bankruptcies, divorces, real estate, and corporate “wind-down issues.”

His ministry at Prisonist.org recently held its 400th meeting. Jeff says about 25% of the people who Zoom in every week are women (yes, women commit white collar crimes, and sometimes they suffer even more shame — “How could you? You’re a woman!”). His group is also starting a new initiative called “Start Here.” The video is pretty powerful.

I asked Jeff what kind of recidivism he’s seen in the 900 people who’ve passed through Prisonist.org over the last several years. “Literally zero,” he tells me. “People who join are committed to change and improve.”

He says the job market is improving — though it’s still not great — but the biggest impediment isn’t the market itself. “It’s the stories we tell ourselves and how we hold ourselves back,” he says, “thinking that we’re not good enough.”

Get “A Little Seasoning”

For anyone leaving prison who was once a professional, Mike Neubig suggests they start with volunteer work and then try to get hired by a nonprofit that has a mission of employing people coming out of the criminal justice system. This will provide what he calls “a little seasoning.” He says if a white collar ex-felon expects to get hired immediately as a manager in the private sector, “you may be disappointed.”

One important factor in the success of all the men I interviewed: Their families stuck with them.

Finally, I had one last question. I asked Jeff Grant if he ever wakes up in the morning and, for a moment, thinks he’s back in his prison cell. He tells me it’s not quite like that. Instead, “I can wake up and just feel terror.” It’s been a long road back, he says, “but I acknowledge I’m one of the lucky ones.”

🌸🌸🌸🌸🌸

How to Survive Prison

I’m reposting tips from the original article… just in case you need this advice someday!

— If you’re going to prison, memorize important phone numbers or have them mailed to you inside. Nobody remembers phone numbers anymore.

— Tell visitors not to handle any cash ahead of a visit, because there may be drug residue on it.

“The single most important thing to know about going to prison is to show respect and be able to receive respect,” says Jeff Grant, who adds that respect is mostly demonstrated by “keeping your mouth shut.” People who ask a lot of questions are suspected of being rats.

Prison has a lot of rules which are not intuitive at first. “It’s like being on a plane and landing in Manchuria,” he says. “You can get off the plane, but you don’t speak the language, you don’t know the customs, you don’t know the culture, you don’t have the money.”

For example, on his third day in prison, Jeff went over to a weight stack to bench press. It was very early in the morning, and nobody was working out.

“Somebody came up to me and said, ‘Are you planning on using that equipment?’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’” The guy told Jeff, “When you’re done, come talk to me.” Jeff said he was so freaked out, he did one bench press before going back to talk to the guy, who suggested Jeff talk to his “cellie,” that is, his cellmate.

When Jeff asked the “cellie” what the deal was, the cellmate told Jeff the man who spoke to him “owns” the weight equipment during that part of the day. “You don’t want to know how he acquired it,” the cellmate told him. “If you want to use that equipment during that time of day, you’ve got to pay him for it.”

Jeff asked why the guy didn’t just tell him that. “He doesn’t know you,” his cellmate said. “He doesn’t know if you’re a rat.” White-collar inmates are generally older and often white, as is Jeff, and that can make other inmates suspect them of being prison plants.

Jeff began to walk the track around the prison yard, 10 miles a day. “After about three months, a ‘shot caller’ came up,” he says, referring to the head of a gang. “He said to me, ‘I hear you can be trusted.’” Jeff knew by now not to speak. “So I just nodded my head, and he said, ‘All right, then.’”

The next day other inmates suddenly started talking to Jeff, asking for legal advice. He ended up helping many of them with divorces and bankruptcies.

“You can’t trust anybody.”

Scott London paid a consultant a few hundred dollars to get advice before starting his prison sentence. “Turns out [the advice] was mostly wrong.”

Here’s what he learned on his own about prison.

“You can’t trust anybody, you can’t trust what people tell you, you have to look out for yourself.” Scott says there will be inmates who want to get you in trouble. At the same time, “Don’t treat people poorly.”

He says the first couple of weeks were a process of learning the rules, such as, “This thing is only for coffee. Don’t wash your hands in that sink.”

Then came the occasional challenges, “where somebody is exerting their influence.” Scott says you can react in one of three ways:

Cowering — “From that time on, they would kind of own you throughout your stay.”

Defiant — “You just go over the top and try and be aggressive with them.”

Something in-between — “Hold your ground and say, ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t mean any disrespect. I’m here to do my thing, you’re here doing your thing.’”

Scott chose the last strategy. “In the end, I made some reasonable friends there that I spent most of my time with.” He says that finding such people helped the time go by. “If you were just trying to be a loner, and you isolate yourself, it’s going to be very, very difficult to get through.”

Thank you, Jane. Your writing is truthful, yet sensitive and inspiring. Your ability to provide a unique perspective on difficult topics is a gift to global journalism.

Great story Jane! As you know I highly appreciate your words of wisdom.