Some Tax Officials Do Uncommonly Well in the Stock Market

A new study finds trading by IRS officials beats the benchmark. Hmmmm.

I’m pretty worked up about this one so I’m gonna get right to it.

There’s a good chance that top-level officials at the IRS are trading stocks based on information the rest of us don’t have (that would be illegal). Either that, or they’re really lucky, because an “abnormal” amount of trades outperform the market. Some of the trades were over $1 million.

How long has this been going on? Why has no one reported it? Because no one ever thought to look at the performance of trades by top tax officials until two accounting professors from the University of Florida helped a graduate assistant pursuing a PhD. The graduate assistant used to do tax work for accounting giant EY. Their findings “suggest that IRS officials possess, and trade on, material tax-related information, and that these trades are associated with future tax enforcement outcomes for the firms.”

I called the authors of the study after seeing a blurb about their research in an excellent blog called Marginal Revolution.

“The IRS knows which years to buy and which years to sell,” Eashwar Nagaraj tells me. He’s the guy who used to work at EY. Shocking, right? “The abnormal returns were surprising to me,” says Prof. Michael Mayberry, one of Eashwar’s co-authors. He adds, “One other faculty member in the department said, ‘There’s no way you’re going to find [these] results.’”

Here’s what they discovered, with help from Prof. Scott Rane.

First, they got their hands on stock trades by senior IRS officials through a Freedom of Information Act request originally made by the Wall Street Journal. They looked at 5,000 trades made by 126 higher-ups at the tax agency between 2016 and 2020. Without getting too much into the weeds (you can read the entire paper here), they began looking at the timing of trades and whether they might be related to tax action (or inaction) by the IRS, information that would only be made public later, potentially affecting a company’s stock price.

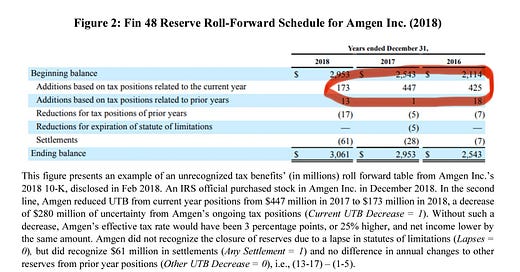

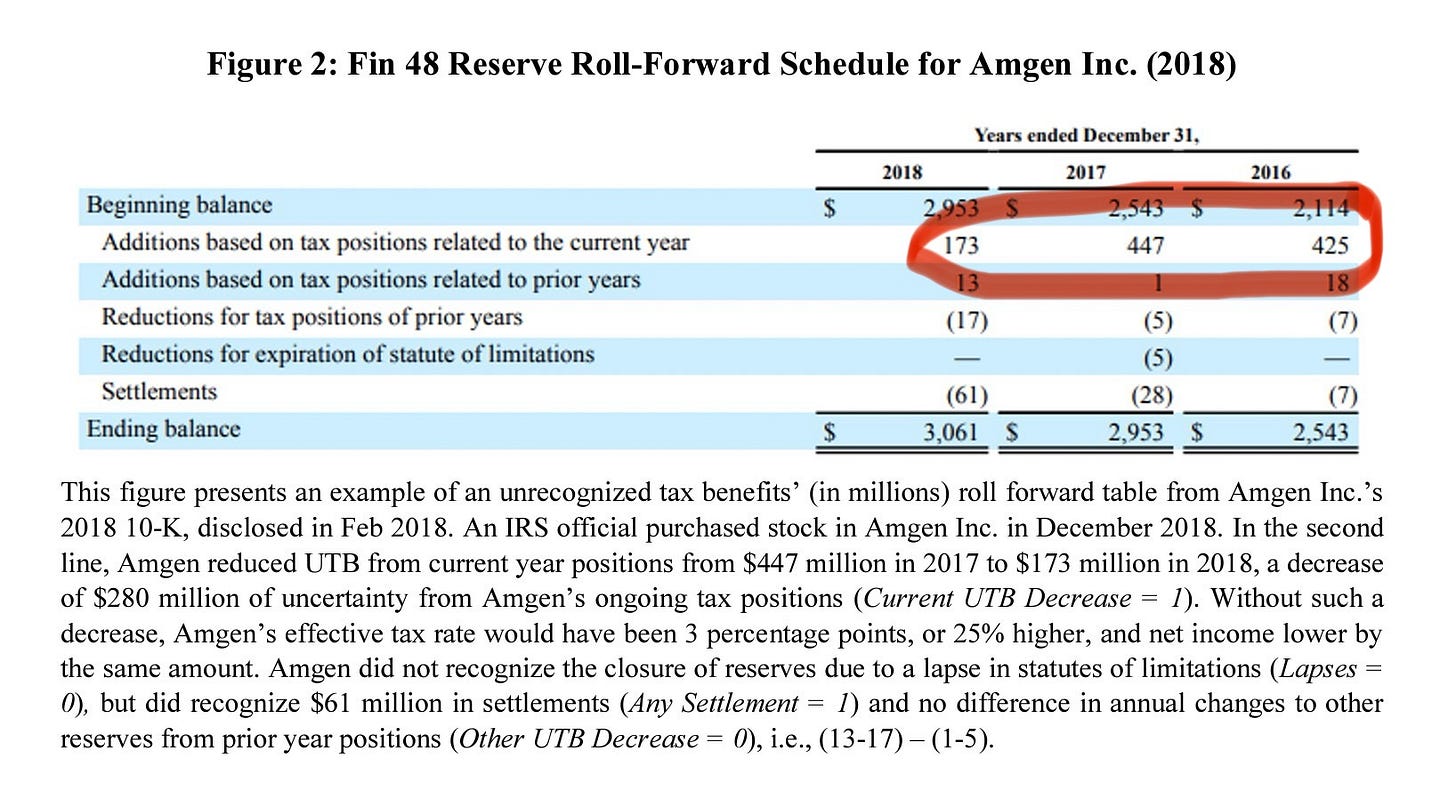

They also looked at how many times a public company mentioned the IRS in its annual report filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (more mentions = bad tax news). And they were especially focused on one figure that only tax geeks might find interesting in a company’s earnings report: how much money the firm set aside in case it gets audited and has to pay taxes for profits booked overseas at a lower tax rate. DON’T GLAZE OVER, THIS IS IMPORTANT. I call this the “just in case I get audited by the IRS” account. The lower the amount set aside, the less likely a company thought they might be audited, or the statute of limitations on a potential audit had run out. Yay! The higher the amount, the more likely the firm might be in trouble. Booo.

Keep Paying Attention!

What the professors found is that a lot of times, like, thousands of times, senior IRS officials were buying shares of companies months before good tax news was made public, and selling shares right before bad tax news came out.

For example, Amgen added a lot of money in its reserve account for potential penalties in 2016 and 2017, over $400 million a year. But the company added significantly less in 2018, only $173 million. That drop indicated good tax news.

At least one person at the IRS bought Amgen stock ahead of the good news going public, according to the study. In the year between the filing of the 2017 and 2018 annual reports, Amgen shares rose 7%, while the S&P 500 rose 2%.

This is the important part. The researchers say that, on average, the successful trades made by the senior IRS officials outperformed the market by as much as 3.5%. That’s a lot. Eashwar Nagaraj calls it “a significant finding… perhaps even larger than [academics] would think is plausible.”

Maybe the guys at the IRS are really smart traders. Eashwar and his co-authors compared the results to similar trades made by higher-ups at the Treasury Department, thinking those people might also be smart about the markets. The Treasury traders did not have the same outperformance based on the same metrics.

But here’s the kicker.

Nearly all of the trades were under $15,000, because (checks blood pressure) it is completely okay for federal officials to make $15,000 trades — it’s considered too small an amount to create a conflict.

“I’m a professor, $15,000 is a large amount of money to me,” Michael Mayberry says. “Maybe it’s immaterial to Jeff Bezos, but these [officials] are not Jeff Bezos.”

Not all of the trades were under $15,000. About 6% of them were really big. Eashwar says that dozens of single trades were over $500,000, or even $1 million. Who at the IRS has that kind of money? “My take is that there’s a lot of lawyers in the sample who are partners in law firms, who do stints at the IRS and then go back to their law firms,” he tells me. Or maybe they come from money, or married into it. Who knows…

Not all trades beat the market (that doesn’t mean they lost money, they just didn’t beat the market). Many things can affect the price of a stock, not just good or bad tax news. Also, some trades were in things like mutual funds, which would not be related to the tax enforcement of one company.

But the authors say one third of the trades outperformed, and all of these trades could be directly correlated to future public information about tax enforcement (or lack thereof). That kind of outperformance is much better than your average hedge fund, where all the smart money is (allegedly). There are about 4,000 hedge funds in the U.S., and the latest data from 2023 shows only 11 funds beat the S&P 500. That’s not even 1%.

“It’s very, very, very hard to beat the market,” says Eashwar. “Investment bankers do not do it on a consistent basis. Even firm insiders are not able to do it perfectly.” (Somewhere, the late, great Jack Bogle and Charlie Munger are smiling in agreement.)

Who Was Trading, and How Often?

The trading happened across several parts of the IRS, from departments responsible for audits, to those in the back office, “like the chief procurement officer, someone who might observe how money is being allocated to audits — meaning, which audits are more likely to happen,” Eashwar tells me. “Some of the most frequent traders in our sample have thousands of trades. They’re picking hundreds of stocks.”

Here’s their breakdown of traders among IRS departments:

The UF professors didn’t reveal the names of the officials whose trades they analyzed. I mean, they’re already poking the bear, you know?

But I asked for an example.

Without naming names, Eashwar says one trader was someone in a department of the IRS overseeing audits of companies trying to book profits overseas at a lower tax rate. One such audit involved “this huge tech company, like one of the biggest companies in the world.” Eashwar says it looked like the audit might go to court and be very public.

He says this one IRS official started selling shares in the tech company ahead of the news, including two sales between $500,000 and $1 million. Then the news broke: “The IRS announced that they’re going to pursue the audit for this big giant tech company.” The penalty could be billions of dollars. The stock fell. A few days later, Eashwar says this same IRS official bought on the dip, making four purchases of the same stock, each worth $250,000 to $500,000.

I’ve made a good living in my career, even by government pay standards, and I don’t know about you, but I would never make a million dollar stock play on a single company.

Unless I knew it was a sure thing.

(I think I know the tech company and the court case. If I’m right, during the year before the IRS announced a court case, the stock went up a whopping 51%. After the news broke, shares fell 8% within a week. Buying opportunity? The stock ended the year up another 35% from that point.)

I emailed the IRS for comment on this study and received no response. When I called the media line, I was told that most likely they wouldn’t be able to comment on employee trading patterns because that’s private.

The authors from UF presented their results in February at a conference by The Journal of The American Taxation Association (um, I missed that one). They made a bit of a splash. Some tax enforcement people from the IRS were scheduled to appear on a panel the next day. Eashwar says he was excited by the chance to talk to them about his paper. (Really? DO YOU KNOW WHO YOU’RE DEALING WITH?). But then the IRS didn’t show. “The people organizing the conference said it was because of the budget cuts,” Eashwar recalls. “They didn’t have the resources to send people to the conference.”

Maybe this is all just a coincidence. The authors say they can’t prove anyone was breaking the law, that anyone was trading on insider information. “We emphasize that we cannot conclude from our analyses whether IRS officials’ trades in our sample violate ethical guidelines,” they write. “However, we document that IRS officials’ trades are informative and associated with subsequent tax enforcement, suggesting that prompt disclosure of IRS officials’ trading activity, similar to those in elected office or corporate insiders, may be beneficial to external stakeholders.”

Officials in the federal government, including the IRS, are required to disclose their stock positions once a year, but they don’t have to list the actual names of stocks they buy or sell, and nobody pays much attention. It’s not easy to access this information. The Government Accountability Office complained about IRS disclosure rules back in 1992.

The authors think officials should have to disclose their trades more often and with more transparency. But they don’t think IRS employees should be barred from trading. “That is essentially a pay cut,” Michael says. It would be even harder to recruit talent if they’re banned from doing what nearly every other American can do. And who wants to work at the IRS as it is? I agree with them. Maybe the tax agency could adopt the policy I had to abide by at CNBC. I was only allowed to own mutual funds or ETFs, I could not hold any individual stocks or bonds. (Fun fact: my portfolio actually did better under this policy.)

The accounting professors hope their study gains traction and that policymakers do something. I asked them the obvious question: Aren’t you afraid now that you’ll get audited? “One of the Twitter comments we got said we’re going to get audited, so I was a bit upset,” Michael confesses. “I didn’t think of it until I saw that tweet.”

By the way, I asked Eashwar and Michael if they’re concerned about whether we might see a spike in unusually profitable trades at the IRS, as employees may be understaffed and overworked in an era of budget cuts. Here’s their careful reply, including the reaction Eashwar received from one of his friends who works at the tax agency:

Nice going Jane. We're seeing too many govt insiders profiting from their position. With the President setting such a miserable example we shouldn't be surprised.

Keep on digging

I'm Shocked. Shocked!